The Walkability Index

I dropped flat on the 13th tee box at Karsten Creek Golf Club, the sun beating down on my face. My water bottle dried up somewhere after the turn and my mouth was full of cotton. Dizzy but conscious, I crawled over to a patch of three-inch rough shaded by the thick grove of oaks.

This was it, I thought. I’m going to die right here – 21 years old… alone… on this damn tee box… on this damn course I had no business playing in the first place. My last thoughts weren’t about my family. They were spent recounting how in the hell I got here…

As the club’s transportation specialist (cart barn boy), I was lucky enough to enjoy playing privileges. And for some reason on this late July afternoon, yours truly decided to walk the course alone. Teeing off just after lunch, the front nine went as planned. I took full advantage of the water coolers strategically tucked away along the cart paths.

But somewhere around the turn (a quarter of a mile walk up a hill and around the corner at Karsten), I started to feel it. I was in the best shape of my life, but no amount of hydration could save me on this day. Instead of calling it after nine, I stupidly pushed on. Around the 11th and 12th holes along the creek, the humidity is oppressive. A hundred yards and 20 vertical feet from the 12th green to the 13th tee was the straw that broke my back.

Maybe if I survive here long enough, a member might stumble upon me. Maybe it’ll be one of the guys or gals on the Oklahoma State golf team, who – after laughing at this pathetic sight – can call up to the clubhouse and send a cart (or an ambulance) for me.

Thirty minutes and no passersby later, I’d recovered enough to stand on my own two feet. I finished the 13th, then took the maintenance shortcut straight back to the clubhouse. Karsten may have won that battle, but I survived to see another day.

Since that time, I’ve been wary of walking a golf course. Not that I don’t do it – but I’m often suspicious of those psychopaths who exclusively shun carts. They probably wear socks to bed, too. How am I supposed to enjoy a round if I’m barely surviving it?

Mark Twain once famously claimed, “golf is a good walk spoiled.” Posthumously, that is, until the quippy line was discovered to have been attributed to no less than seven others. No matter the origin of the quote, its spirit rings true in this author’s bones.

In a game full of choices (shorts or pants, send it or lay up, Caesar wrap or hotdog at the turn), the first – and possibly most important – choice of the day is encountered from the onset.

For me, a husky fellow who is riddled with creaky knees from years of church league basketball, that answer is easier than most – if a cart is available, you’ll probably find me in it. But there are many “purists” out there who would admonish me for such a decision.

“You’re lazy,” they may chide, never knowing the hurtful impact of their slanderous statements.

(Laziness is subjective. Energy levels, however, are objective according to the laws of quantum mechanics, and I choose to conserve mine for the far more important decision of never laying up.)

And while these pretentious folks sashay about the golf course on their fleet feet, I choose to take the high road. Because at the end of the day, it’s a choice. MY choice. Whether to survive the walk, or to thrive in my game.

But HOW do you choose? Some may want to walk, but are afraid they may regret the choice somewhere deep in the round. After years of struggling with this myself, I developed a proprietary algorithm that helps me answer that question before I ever get off the couch.

Enter: The Walkability Index

I wanted to assign an objective walkability score to any given golf course. I say objective because there are groups out there (looking at you, Walking Golfers Society) who use subjective ratings like “Course is easy to walk” and “Course is essentially unwalkable.” Just like some might think climbing to the top of Mt. Everest is manageable, it’s an impossible task for someone of my fitness level. With an objective rating on a scale of 100, one can determine their own threshold for walking a golf course. If there’s a track over 70/100 on the Walkability Index, I’m seriously considering the riding option.

The five factors by which a Walkability Index is determined are:

Total Length Walked (the distance measured from the tips of the first tee to the 18th green assessed by natural walking paths and middle of the fairway – not necessarily cart paths)

Total Elevation Gained + Lost (the sum of elevation gained walking up hills and lost walking down hills)

Average Slope

Max Uphill Slope

Max Downhill Slope

The grading system is simple - each factor is graded on a 1-10 point scale. The sum is multiplied by 2 and that total out of 100 is the Walkability Index for that course. Here are a few examples:

Lake Hefner (South), Oklahoma City, OK

6405 yards on the scorecard

Total Length Walked: 4.22 mi

Total Elevation Gained + Lost: 521 feet

Average Slope: 1.9%

Max Uphill Slope: 9.3%

Max Downhill Slope: 9.1%

With these factors plugged into the algorithm, Lake Hefner South’s Walkability Index is 40/100. This is a straightforward municipal golf course that could be walked by most any day of the week.

The Patriot Golf Club, Owasso, OK

7158 yards on the scorecard

Total Length Walked: 6.26 mi

Total Elevation Gained + Lost: 1,543 feet

Average Slope: 3.7%

Max Uphill Slope: 24.2%

Max Downhill Slope: 24.1%

The algorithm gives The Patriot a Walkability Index of 98/100. It is technically walkable, but do you want to?

Again – not scientific and there are other factors at hand that aren’t taken into account, like soil conditions, temperature and humidity, etc. But I think this is a simple way to determine what is feasibly and enjoyably walkable for YOU. I’ll leave you with a few others.

Karsten Creek Golf Club

7417 yards on the scorecard

Total Length Walked: 5.47mi

Total Elevation Gained + Lost: 1,416 feet

Average Slope: 4.2%

Max Uphill Slope: 25.4%

Max Downhill Slope: 19.1%

Walkability Index = 92/100

Southern Hills Country Club

7184 yards on the scorecard

Total Length Walked: 4.74 mi

Total Elevation Gained + Lost: 900 feet

Average Slope: 3.2%

Max Uphill Slope: 18.0%

Max Downhill Slope: 20.7%

Walkability Index = 70/100

Pinnell’s Playground

It’s a warm, clear early Autumn evening. Matt Pinnell is working his way through a throng of guests during a luau-themed celebration in his honor on Monkey Island.

If you were dropped into the middle of this scene, it might be a shock to your senses. This isn’t an island (it’s a peninsula), there are no monkeys (at least none that I saw) and we’re not on Maui. That doesn’t matter. No one here on this night would prefer the sandy beaches of Hawaii over this time and this place – especially Pinnell.

He’s in his element. Donning a brightly colored shirt and a lei around his neck, Pinnell works the crowd masterfully. There aren’t many in the room he doesn’t know by name, and by the end of the night he’ll work that number down to zero.

It’s a lively group here this evening. We’re at The Anchor Sports Bar at Shangri-La Resort and Golf Club. I’ve been up here once or twice before as a kid, but this is NOT what I remember. What was once a location considered an afterthought by many Oklahomans, Checotah native Eddy Gibbs – a self-proclaimed fence builder – has invested millions into revitalizing this resort over the last 10 years (I should’ve gotten into the fence business).

Inside by the bar, many attendees are catching an early-season football game on one of the many vibrant televisions. Out on the patio, the sun is setting and the buffet line is growing. Gibbs calls this part of the resort “The Activity Park.” There’s an arcade, golf simulators, basketball courts, cornhole pits and even a wiffleball field designed to look like a miniature Fenway Park.

Tonight, it’s a party. Tomorrow, we hit the golf course.

It’s a crisp morning on the island. The sun hasn’t broken the horizon when the first golfers start to trickle into Shangri-La’s grand clubhouse. There’s a pan of breakfast burritos and a carafe of steaming hot coffee. One-by-one, participants sign in, grab a gift bag, load up on breakfast and head out to the range. It’ll be a full day of golf on a historic track along the banks of Grand Lake, and Pinnell can’t stop grinning from ear to ear.

It's not because of his swing; he carries a 12-15 handicap and doesn’t get to play as much as he’d like (“I’ve got four kids at home, so when I can play, it’s usually when I’m traveling somewhere,” he says). It’s not even about the prime conditions this morning has in store. Pinnell’s smile is a reaction to a driving range full of like-minded individuals who have come together to support and show appreciation for one of Oklahoma’s most ambitious revitalization projects.

The resort has been a staple on Monkey Island for nearly 60 years. The original hotel was opened in May 1964 by Oklahoma City’s Frank Richards. Management changed hands multiple times before falling to Wichita native Charles Davis in 1969, who owned 1000 acres and ran Angus cattle on the island. For the next two decades, Davis transformed the sleepy fishing lodge into a world-class resort, earning sought-after accolades such as Mobil’s Four-Star designation and AAA’s Four Diamond Award.

The resort was billed as a “Mini-Hawaii” on the tip of Monkey Island. The Tahitian Terrace became known for its live music and free-flowing tropical libations. The cattle baron even built 36 holes of Championship golf on the island, attracting some of the area’s biggest golf enthusiasts. Hall of Fame New York Yankee Mickey Mantle frequented the resort in his retirement years, hosting the “Mickey Mantle Celebrity Golf Classic” there from 1991-1994 to benefit the Oklahoma Make-A-Wish foundation. The attendee list for these events read like a “Who’s Who” of influential people in American sports and culture - Bob Knight, Stan Musial, Yogi Berra, Bob Costas, Neil Armstrong, Willie Nelson, Bill Murray, Warren Spahn, Allie Reynolds, Steve Owens, George Frazier and Eddie Sutton.

A newspaper advertisement for Shangri-La in 1975.

The ties between Shangri-La and Oklahoma’s political landscape run deep. In 1977, the resort hosted the Midwestern Governors’ Conference. Oklahoma Lt. Gov. George Nigh acted as master of ceremonies for the three-day event, showcasing the resort and its various amenities. Following the event, journalist John Young stated, “The setting, on Grand Lake O’ The Cherokees, undoubtedly was a pleasant surprise to visitors unfamiliar with Oklahoma… It was surely a big plus for the state’s effort to upgrade its tourism industry.”

The positive reaction of the event lingered as five years later, Shangri-La was once again chosen to showcase itself on the national stage.

Nigh, now the Governor of the State of Oklahoma, convinced the National Governors’ Conference to hold their annual meetings at the resort in 1982. Davis pulled an additional $25 million in resources together to expand and improve facilities in advance of the event. Attendees included Pierre S. du Pont IV of Delaware, Bill Clements of Texas and John D. Rockefeller IV of West Virginia. In all, 41 governors from around the United States attended the conference on Monkey Island.

If the National Governors’ Conference of 1982 was a high point for the resort, then the ensuing three decades were a roller coaster. Falling into bankruptcy in 1986, the property changed hands multiple times and much of its assets fell into disrepair. Shangri-La became merely a distant memory to many who had once held her in such high regard.

Enter Eddie Gibbs.

In early 2010, the fence magnate purchased the property with one goal in mind – to create a world-class golf resort at Grand Lake. Within 15 months, Gibbs and his team had begun to revitalize the Championship Blue Course and built the towering 13,000-square-foot clubhouse. By the end of 2011, The Champions Nine was open for play. By the summer of 2013, Shangri-La boasted 27 holes of Championship golf.

“One of the reasons we champion the efforts at Shangri-La is Eddie Gibbs’ investment back into a gem of a property inside the state of Oklahoma,” Pinnell said. “We’re always trying to highlight entrepreneurs and developers who take a tourism attraction that may have been hot decades ago and revitalize them. If you build it; they will come. If you demand more than just being ‘OK’, then Oklahoma taxpayers will reward that effort.”

It's because of Gibbs’ efforts to revitalize a place that holds historic value to the state of Oklahoma that Pinnell is excited to host his golf tournament there each year.

“I hear stories of people who come to my tournament who haven’t been to Shangri-La in decades or have never even been to Grand Lake before. I love hearing that someone came to my tournament and then tell me that they brought their wife or their family out there the next weekend.”

Pinnell has served as Oklahoma’s lieutenant governor since 2019. But when asked about his day-to-day, you might be surprised by the answer.

“The lieutenant governor position is a blank slate – it’s kind of what you make it,” Pinnell says. “I ran on a platform of tourism four years ago and we won all 77 counties because of that.”

He compares his platform to that of Nigh, who in 1958 became the youngest lieutenant governor in state history at age 31. During his tenure, he was noted to be Oklahoma’s greatest cheerleader, pushing the state’s agenda of tourism. As a state legislator, he introduced a bill to make “Oklahoma!” the state song. He was also known to entice movie producers to film on location in Oklahoma. During his time in public office, Nigh saw films such as “Where the Red Fern Grows,” “Rumble Fish” and “The Outsiders” filmed in Oklahoma.

“He was – and still is – one of the best promoters and champions of our state,” Pinnell said. “And that shouldn’t be discounted. We need somebody in the Executive Branch who understands sales and marketing, because if we don’t define who we are as a state, then 49 other states will define it for us.”

That’s the main reason why Pinnell wanted so badly to hit the ground running. One of his first efforts as lieutenant governor was to establish a consistent brand for the state of Oklahoma. This project brought together some of Oklahoma’s brightest and forward-thinking minds in marketing, sales and communications to develop a visual and verbal identity that the state could utilize. The result can be found on welcome signs at every major highway that enters and exits Oklahoma, on agency websites and on buildings around the state.

“When we came in, we realized the wide perception from people outside our state is ‘Oklahoma is a flat dust bowl,’ and nothing could be further from the truth. But most people didn’t know that because we weren’t promoting a positive, diverse brand. So we got 200 Oklahomans together for a volunteer-led effort to identify that brand.”

On the heels of the new brand came none other than a worldwide pandemic. For Pinnell, he saw a tremendous opportunity. His team launched #OKHereWeGo, a digital campaign designed to market Oklahoma’s outdoor assets, from hiking and camping to fishing and – of course – golf.

“That gave us an opportunity to show people what was 30 minutes outside their door,” Pinnell said. “From golf courses to state park trails, a lot of people were looking for things to do. Out of a crisis, sometimes there are positives, and I think one of those was Oklahomans got outside again.”

#OKHereWeGo was a campaign designed to get people to enjoy outdoor activities like golf, fishing, hiking and more.

From the initial push to get people outside, now Pinnell and his team are implementing opportunities to sustain that momentum. One of those ways is through the newly formed Oklahoma Golf Trail.

With newly passed legislation widely supported on both sides of the aisle as well as Pinnell’s office, a commission will designate a list of golf courses around the state that will be highlighted on the official Oklahoma Golf Trail, something that he is excited to market in the future.

Pinnell is not lost on the rich golf heritage that Oklahoma boasts. From the highest concentration of Perry Maxwell golf courses in America to the slew of major championships Oklahoma has hosted, he understands the unique opportunity we have to market the game of golf.

“Tourism is the front door to economic development,” Pinnell said. “Whether it’s a major championship or the college softball World Series, every event we can host will draw people to our state. What I know for a fact is that Oklahoma sells very well when we can actually get people to the state.”

“That’s what was so powerful about the PGA Championship,” he continues. “It’s on TV every day, so millions of people are seeing that Oklahoma is in fact not a dust bowl and actually a beautiful place, but the tens of thousands of people who visited Tulsa for the first time – I’d bet you anything that most of those people will be back because they saw a really cool city.”

The full result of Pinnell’s efforts remain to be seen; he’s hoping for another term to continue building on that momentum. But he’s also acutely aware of the public/private partnerships that are necessary to sustain that growth.

“The state government can only do so much,” Pinnell said. “A city can only do so much. You see these golf courses or any sort of city- or state-operated recreation, you really do need private partners in that effort. I am much more sensitive to seeing and recognizing those private and corporate efforts. Having a corporate partnership could mean the difference in keeping a golf course open or not.”

I have to leave the tournament early, so I’m not around to see Pinnell’s team finish in the middle of the pack. I did, however, get the chance to tour Gibbs’ latest effort at Shangri-La, “The Battlefield” – an 18-hole Par Three course that will offer dramatic green complexes and approach shots ranging from less than 80 yards to nearly 250 yards. It’s a project that superintendent Justin May is eager to see completed.

“I really think this will be a game-changer for golf tourism in northeast Oklahoma,” May told me as he drove me around the new track.

Driving off the island and back into reality, I reminisce back to the previous night’s luau, when I pulled Pinnell aside to thank him for the invitation. The sun had set and we were watching resort guests play pickleball at The Racquet Club, another gem of Gibbs’ island playground.

I asked him about reelection – he’s on the November general election ballot - and what’s next for him as lieutenant governor.

“Wherever your focus is as an elected official is where you’ll see movement,” Pinnell answered. “We didn’t have a standalone Secretary of Tourism before I asked for it. If you think about that, we didn’t have someone in the Executive Branch who every single day was trying to promote the state. I can’t say what other elected officials would or wouldn’t do to draw continued interest to our state. But I can tell you for a fact that right now, Oklahoma has a lieutenant governor who is passionate about our efforts in golf and outdoor recreation, and I’m going to try and leverage that passion into creating more revenue for our state.”

Whatever his future holds, I’m comforted to know that this mid-handicapper will continue to be an advocate for the game of golf in Oklahoma.

Way Out West

The complicated history of Boiling Springs Golf Club and one man’s mission to restore her glory.

Editor’s Note: A special thank you our friends at The Golfer’s Journal for allowing us to document their event at Boiling Springs Golf Club in June 2022 and to Matt Hahn for contributing his outstanding photography to this story.

There’s a few things you need to know if you’re planning a trip out this way.

1. Out here, distance isn’t measured by miles, but rather by time. Old-timers will tell you that you’re a couple of hours from “The City.”

2. “The City” is Oklahoma City, by all bucolic intents. Tulsa is just Tulsa. In reality, this place is 150 miles from The City, and 200 on the nose from Tulsa.

3. You’re going to have plenty of time to think.

On the way out, you may have noticed a brief respite from the otherwise persistent rolling prairie at the Gloss Mountains (not Glass) or taken a detour to visit natural phenomena boasting larger-than-life titles like “Little Sahara” or “Great Salt Plains.” But the rest of the trip leaves you ample time for reflecting on what’s ahead.

“Just off the beaten path” doesn’t do this journey justice. You won’t accidentally stumble on this place. Like generations before you, the pioneering spirit hits you somewhere between Ringwood and Mooreland. To stretch your legs, you stop at an unnamed cemetery somewhere in the vast six million acres of the old Cherokee Outlet to track down the grave of your great, great, great grandfather. Now segregated by miles of barbed wire, this used to be open range. Legendary cattlemen drove millions of Texas longhorns across this land along the Chisholm and Great Western Trails. Your mind begins to wander as you try to imagine the daily perils those early settlers dealt with...

The headstone of William Ely, Sergeant in the Union Army and 3X great grandfather of this author. He settled land along the Cherokee Strip in the late 19th Century, less than 40 miles from present-day Boiling Springs State Park.

Suddenly, like a mirage against the endless expanse of Southern Great Plains savanna, a heavily timbered spread rises on the horizon. Thickets of invasive eastern red cedars have overtaken much of the vegetation, but remnants of the area remain. Unique rock formations. Sandsage grassland. Dust Bowl-Era constructions. A steady flow of crystal-clear water bubbling from the ground.

Archeological evidence estimates that humans have inhabited this region of Oklahoma for more than 14,000 years. Bone scatter along the nearby Beaver River suggests that Paleoindians used the region as a kill site, driving hundreds of American bison off cliffs and into “arroyo traps,” spearing and butchering the noble brutes for every available resource.

The first written record of this area appears as early as 1541, when Spanish explorer Francisco Vazquez de Coronado visited in search of the “Seven Cities of Gold.” A century later, Juan de Oñate reported Indian encampments along the cool, natural springs. A fur trading post was established in 1823 by U.S. Cavalry General Thomas James, and pioneers began flocking to the area.

In 1868, as Young Tom defeated Old Tom by three strokes in the ninth playing of The Open Championship at Prestwick, Col. George Custer set up camp on the other end of the county at Fort Supply. From there, he would plan and execute his government-endorsed annihilation of Black Kettle’s Southern Cheyenne camp on the banks of the Washita River.

But it wasn’t until 1935 – on the cusp of the greatest human-influenced natural disaster – that Boiling Springs State Park began to take shape. On the backs of 350 men in Company 2822 of President Roosevelt’s Civilian Conservation Corps in the throes of the Dust Bowl, the park began to form. In the span of four years, through torrential dust storms and record heat, these men labored day and night moving rocks and establishing this oasis at the doorstep of No Man’s Land.

This land requires resilience. Naturally exposed to classic American Interior Plains elements, record temperatures in the area range nearly 140 degrees Fahrenheit. Hail the size of baseballs is common in the spring. In 1947, a 1.8-mile-wide tornado hit the nearby town of Woodward. At 8:42 p.m., the twister – which had traveled for nearly 100 miles to this point – entered city limits. In moments, 100 city blocks were wiped to their foundations. More than 1,000 homes and businesses were destroyed. In Woodward alone, 107 people were killed and 1,000 injured.

The state park is situated on the banks of the North Canadian River, which separates the Anadarko Shelf from the Anadarko Basin. Along the river’s corridor, rock formations date from the Cenozoic Era – more than 66 million years ago. Doe Creek Limestone serves as bedrock for collecting ground water. Once the underground water meets the topography of the land, a natural spring is formed.

They’re called “boiling springs” not because of the heat – they are in fact quite cool – but rather the way the water bubbles up from the earth. While you’re not here for a science lesson, it’s important to understand this phenomenon. Because instead of the hard clay soil Oklahomans know all too well, these springs beget a soft, sandy loam.

Adjacent to the park, yet sharing most of its natural resources, lies your destination. Down a winding road with a smattering of private homes, you emerge from a thicket of trees to find the understated clubhouse on the south end of a parking lot. A handful of carts are pulled out of the barn – which is more like an open-air shed that doubles as a picnic area. At first glance, nothing about the scene surprises you. This is your run-of-the-mill muni golf course in rural Oklahoma, where denim is often the attire of choice and Coors Light is the preferred cocktail.

The clubhouse is sparse. You notice the framed photos of the various high school golf programs that call this place home. On the right, there’s a sale rack with an unassuming collection of hats, towels and maybe a polo or two. The young lady at the front desk welcomes you, confirms your tee time and accepts a pair of twenty-dollar bills you slide across the counter. You stock up on a handful of crispy domestics and head outside to roll a few putts. There’s no driving range, but at 6,500 yards, you convince yourself it’s unnecessary.

After a few putts, you step off the 20 or so paces to the first tee. Looking south toward Texas, the first is as straight as an arrow. The hole’s only resistance, a trio of fairway bunkers that pinch the short grass to just eight yards wide, is often rendered defenseless by the long hitters. It’s when you find the putting surface that you begin to realize the Maxwellian influence golf course architect Donald Sechrest may have had when he designed the place in 1979. From the first green, you can hit a high wedge onto the tee boxes of No. 2, No. 7 and No. 18 and the sixth and 17th greens. This confluence of holes is a classic Perry Maxwell characteristic, who utilizes similar routings at notable tracks like Dornick Hills, Southern Hills and Prairie Dunes.

The Prairie Dunes connection may go even deeper, however, as it was a favorite course of the native-Oklahoman Sechrest. In 1964, 15 years before he built Boiling Springs, Sechrest was noted to have made a trip to the Hutchinson, Kansas site with three other Stillwater residents, Joe Adair, Theron Covey and Cmdr. Dugan Roberts. He was an assistant professional at Lakeside Golf Club at the time, working for his former college coach, Labron Harris Sr., and completing his first design which would become Stillwater Country Club.

It's not until the second hole that you start to discover the unique nature of this place. A 350-yard dogleg right par four, you send your drive through a chute of oaks and black walnuts. Anything that strays from the fairway will find a soft, sandy waste area that dominates this landscape. For the next few hours, you’re tasked with navigating this wild, untamed land.

Untamed as it might seem, that’s the furthest from the truth if you ask Jeff Wagner. Slender and bearded, Jeff has served as general manager and superintendent of the golf course going on eight years. Sporting a slightly thinned hairline styled in a classic buzzcut, Jeff wears so many hats at Boiling Springs that it doesn’t matter.

From marketing to finances and even the in-house mechanic, he touches nearly every aspect of the business.

“I’m NOT the golf pro,” he clarifies. “But I can fold a mean sweater.”

Boiling Springs’ jack-of-all-trades, Jeff Wagner.

This place was different from the beginning. Built with prison labor, one of the first assistant superintendents was a former inmate with the Oklahoma Department of Corrections who, before the project, hated golf. The course was one of the first in the state to utilize treated sewage. Rather than dumping the activated sludge into the river, it was pumped from town to water the grass.

Del Scoville, the first head pro, claimed, “if it wasn’t going on the golf course, it’d be in the river and going to the people in The City to drink.”

Tight and menacing, it took more than a year before anyone broke par. Eastern red cedars have always been a part of the story, but the 80s and 90s saw an explosion of the invasive tree. Hundreds of thousands sprang up on the property, choking off the grass and other flora. What wasn’t decimated by the trees was polished off by the pervasive nematode population.

For the first five years, Jeff and his team waged an all-out attack on this foreign enemy of the east. With two chainsaws, a tractor and plenty of willpower, they ripped the trees from their stronghold, reconfigured watering routes and peeled back the layers of this landscape, revealing towering sandy blowouts and prized species of flora.

Let me explain something: When I said “team,” I meant Jeff and his sidekick, Ivan, a kid who grew up down the road in Mooreland. That’s it.

In a land that Daily Oklahoman journalist Joyce Peterson once called “a worthless stretch of tangled woods, briars and brush,” Jeff and Ivan have gradually uncovered a work of art. The tree eradication is ongoing. There are still years of work to be done. But in Jeff’s words, “we’re closer to the end than we are the beginning.”

Like a man tasked with restoring a lost Rembrandt, Jeff made the decision to reduce his maintained acreage from 65 to 45 acres. With the remaining 20 acres, his team added yuccas, sunflowers and a mix of blue grama, sideoats grama and little bluestem that are naturally found in Western Oklahoma. In a few arduous years, this effort has reestablished the natural beauty of this area.

In a niche society where naturalization and minimalism are glorified, Boiling Springs has found a way to maximize its assets.

Sure, you can tell yourself you’re “roughing it” at pseudo-minimalist golf meccas in Nowhere, Wisconsin or Boondocks, Oregon. You can kick off your Jordan 4s at the end of a $400 round and head to dinner at some restaurant with a millennially-influenced name like “Forge” or “1895” or “The Tufted Puffin,” where you’ll no doubt enjoy an $85 grass-fed ribeye and a wine list the size of an Oklahoma history textbook before retiring to your rustic-yet-elegant cottage, complete with feather-top bedding and wet bar. Spartan in design. Garish in amenities. That’s great if you’re into that sort of thing.

This ain’t that.

Boiling Springs, by all accounts, is a purely unadulterated golf experience. In no way, shape or form is there an effort to compromise or deviate from the norm of Oklahoma hospitality.

“We have what everyone wants,” Wagner says. And it’s true. Forested sand dunes and dramatic vertical relief are the golden tickets for modern golf enthusiasts. It’s the reason why more and more are willing to travel to no-name communities to get their fix.

For a hundred-dollar bill, Jeff will let you play all you want at Boiling Springs AND give you a hotel room in town with enough cash left over to buy yourself an Oklahoma-bred porterhouse at Al’s Steakhouse on Main Street.

No caddie fees. No dress requirements. No nonsense.

You want sand-based golf? Got it.

You want wildlife? Watch out for cantankerous wild turkey and bad-tempered bobcats.

You want to slam a couple cold ones as the sun sets behind the dunes while Long Hot Summer Day blasts across the 18th green? Be sure to save one for Jeff.

As you wind your way through the dunes, you become intensely aware of your surroundings. The constant Western Oklahoma wind whips at your face. The rumble of a train travels along the distant tracks. A rodent burrows itself into the sand.

Supplied with a torn and tattered canvas, Jeff has reestablished this property’s assets - sandy blowouts, native grasses, unique topography and the best set of $30 bentgrass greens on the planet. His diligence and dedication to the land have revealed a hidden chef-d'oeuvre.

Forget restoring the lost Rembrandt. Maybe he is Rembrandt.

The Entirely Unlikely (But True) Story of Southern Hills Country Club

“The only things we keep permanently are those we give away.” – Waite Phillips

Early sketch of SHCC by Paul Corrubia

Waite Phillips wasn’t about to fork over his money to the two businessmen who approached him about financing a new country club in Tulsa.

This was the Great Depression, after all.

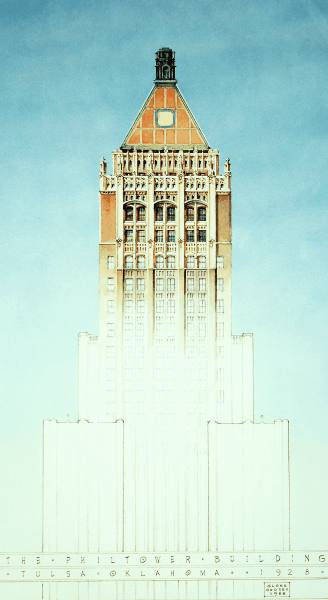

The oilman-turned-banker had already made a name as one of the wealthiest men in Tulsa and - for that matter - all of America. His endeavors alongside brothers Frank and L.E. to build Phillips Petroleum Company before going about it on his own had made him millions, and his impression on the city was everywhere. From his downtown office buildings (aptly named the Philtower and Philcade) to his 72-room Italian Renaissance-style mansion near 31st and Peoria, Waite Phillips had already made his mark on the city.

He arrived in Oklahoma in 1911 at his brothers’ behest. Frank and L.E. had been risking everything for eight years in Bartlesville territory at this point. They drilled their first gusher, the Anna Anderson (named after the eight-year-old Delaware Indian girl who held the land lease) in 1905 and organized the largest bank in town, Citizens’ Bank and Trust, to offset the volatility of their drilling ventures. The Phillips family struck it rich, and Waite wanted his own piece of the pie.

His time in Bartlesville lasted just four years before Waite set out on his own. Moving to Tulsa, he began a career as an individual oil producer. A decade later, he sold most of his holdings to the Barnsdall Oil Company for $25 million.

While he was driven to succeed in his career, his passion was for the land. In 1929, he acquired 770 acres south of Tulsa to be utilized for family recreation and horseback riding. The spread, historically a part of the Creek Nation, covered section 32-19N-13E and section 5-18N-13E along present-day 61st Street and Lewis Avenue. This plot featured dramatic land movement, rising more than 150 feet in elevation in the southeast corner and falling away toward the Arkansas River. A meandering tributary center-cut the property, delivering rich nutrients to the soil beneath.

It was prime real estate at a time when real estate wasn’t prime.

Waite Phillips with his wife - Genevieve - and children - Elliott and Helen Jane at Villa Philbrook.

In 1934, Tulsa businessmen William (Bill) K. Warren and Cecil Canary were two disgruntled members of Tulsa Country Club, an A.W. Tillinghast design northwest of downtown located on the property of prominent Tulsan Dr. S.G. Kennedy. The grip of the Depression had taken hold across the country, and while some Tulsans were insulated to the majority of its effects due to their oil holdings, it was being felt strongly in banking and land ownership. That was the case with Kennedy, who was rumored to announce in the fall of 1934 that once the club’s latest lease on the land expired in 1936, he planned to sell the property.

This would have been a disaster for the club’s current members. What was once a safe haven for Tulsa’s societal highbrow was now on the brink of being shuttered - or worse - flooded by hackers, duffers and ruffians. More speculation arose when members of the Hy Hat Club (Tulsa’s equivalent of the legendary Halcyon Society in Bartlesville, of which Waite’s nephew was a member) began showing up dead on the streets of Tulsa’s posh neighborhoods. Phil Kennamer – the son of a federal judge – was charged with the slaying of John Gorrell – the son of a prominent Tulsa doctor. Kennamer fired two rounds into the back of Gorrell’s head at the intersection of South Victor Avenue and East Forest Boulevard, just a few hundred yards from Waite Phillips’ home, Villa Philbrook. Days later, Sidney Born – the president of the Hy Hat Club and the individual who drove Kennamer to the eventual murder scene – was found dead of an apparent suicide.

Tulsa’s upper echelon was in a panic. One reporter noted, “Have Tulsa’s young been destroyed by their own indulgences? Are they sated and aged before their time? Have they seen and done everything while still in their teens so they must seek in shadowy places for new thrills?”

The same article reported that “one exclusive club for adults sent out a confidential letter to its members asking if they wished to sponsor a series of planned – and supervised – entertainments for Tulsa’s young.”

Those who socialized at the Tulsa Club downtown and golfed at Tulsa Country Club saw a potential opportunity. They formed a plan to merge the two clubs and expand the footprint to include Kennedy Golf Course, a 1925 Perry Maxwell-designed public course adjacent to Tulsa Country Club. This would give members the opportunity to expand their family-friendly activities, including polo, tennis and swimming.

While the group appointed Warren to negotiate a workaround with Kennedy, they made it clear that they weren’t above looking at alternative options. On Dec. 4, 1934, Warren wrote a letter to Phillips, boldly asking the banker to finance a new facility on behalf of the “Tulsa Town and Country Club.” The Kennedy deal nearly happened, but at the last minute for reasons lost to time, the merger fell through and members were left scrambling for other options.

An announcement in The Oklahoma News on December 24, 1934.

Warren knew of Waite Phillips’ property south of town. He knew it was premium land, ideally suited for activities of the day. On Dec. 26, 1934 – two days after it was reported that the Tulsa Country Club would vote on a merger with the Tulsa Club, Phillips summoned Warren to his office to discuss the alternative plan of building a new club on his property. Warren was nervous about facing Phillips alone, so he brought along Cecil Canary for moral reinforcement.

Tulsa businessmen R. Otis Mclintock, Cecil Canary and William K. Warren, Sr.

On the 21st floor of the Philtower – the E.B. Delk-designed gem of the Tulsa skyline, Warren and Canary stepped into Phillips’ cavernous office. A buffalo hide spread across the floor. Chandeliers hung from the arched ceiling. A blue-tiled fireplace lined the wall behind his desk, cluttered with a smattering of letters addressed to the banker and financier.

“Every paper you see here contains a request for money to help start a business venture or support a worthy cause,” Phillips started in on the men. “Not all of the business ventures are worthy of much consideration, Mr. Warren, but yours is ridiculous!”

Bill and Cecil were shocked at the response. Did he not believe in the family values that country clubs offered? Could he not see that Tulsa was starved for wholesome sporting activities? Just when they felt like jumping out the window to spare themselves any more embarrassment, Phillips softened his tone and entered negotiation mode.

“I have a counter-proposal. If your group will pledge to spend $150,000 in two years – one half to be spent the first year to construct the family-type country club you described in your letter, I will donate the three hundred acres you need. However, I will not put up one cent to help build the facilities.”

Warren and Canary left Waite Phillips’ office that day with a formal written offer from the oilman and banker, but little hope that they could actually fulfill his demands.

The letter provided more detail – by January 15, 1935, just 20 days after their meeting, they needed to have 150 commitments of $1,000 each. While both men were considered wealthy by the day’s standards, neither felt comfortable writing a $1,000 check. How they were going to find and convince 148 others to do the same in less than a month was beyond the realm of their imagination.

Another proviso in the letter was where the clubhouse was to be located on the grounds. It stated: “As part of this proposal I stipulate that the main clubhouse must be located approximately in the center of the south line of the acreage used for club purposes. This location was recommended as most desirable by Perry Maxwell when he made a preliminary survey a year or two ago.”

This is the first mention of Maxwell in relation to Southern Hills. It turns out Warren and Canary weren’t the first to approach Phillips with the possibility of building a golf course. In 1933, the golf course architect first proposed to Phillips links on the land. According to Maxwell’s second wife, “He had the rare ability to see a golf course nestled among scrub oaks. He did not like to disturb the land, and it was because he fell in love with this beautiful piece of property that he begged Waite Phillips to allow him to build a course on the land.”

At this point in his career, Maxwell was well-known as a golf course architect. Through his previous banking career in Ardmore, Oklahoma, he knew the Phillips family well. Nearly ten years prior, he designed Hillcrest Country Club in Bartlesville for Frank, L.E. and the prominent oil barons that made up the Halcyon Society. This connection, coupled with his propensity for sticking to a timeline and a budget, made him Waite’s choice for building the golfing grounds of Southern Hills Country Club…if it ever actually got off the ground.

If the project failed, it wouldn’t be for lack of trying. Warren and Canary immediately consulted with Otis McClintock and other interested members from the Tulsa Club and Tulsa Country Club. George Bole, another Tulsa oilman, hosted the first dinner party at his 14,000 square foot Oakwold Mansion catered by John Mayo of the Mayo Hotel.

One hundred and twenty-five prominent Tulsans attended the dinner party and the group elected the first board of governors for the club: Foss Parriott was elected president and S.C. Canary, Rush Greenslade and C.H. Lieb were vice presidents. Jack Padon was elected secretary-treasurer and directors included Bill Warren, Don C. Bothwell, Jack L. Shakely, C.W. Flint, Dudley Morgan and Otis McClintock.

When the dinner party ended, the club had 74 signed pledges…but just three were accompanied by $1,000 checks. All they needed at this point, though, was the signatures. These were the days when a handshake meant something, and they trusted the men who signed pledges to follow through.

By January 14, Bill Warren presented Phillips with a list of 140 men who pledged $1,000 each. Despite being 10 signatures short of their goal, Waite accepted the offer, knowing how difficult this task had been. When the new club was announced, Dr. Kennedy was so upset that he withdrew $600,000 from Phillips’ and McClintock’s First National Bank.

Meetings of the newly formed Southern Hills Country Club board of directors were held in three locations – the Tulsa Club at the corner of 5th and Cincinnati, Foss Parriott’s home near 31st and Lewis and Otis McClintock’s home on the corner of 41st and Lewis.

Don Bothwell, affectionately known to early club members as “Old Rooster,” was selected to be the golf course committee chair. It was he who ultimately tabbed Perry Maxwell to lay out the links – naturally with a nod from Phillips. Within days of the deed being handed over to the club, Maxwell was on-site. Old Rooster was intimately involved in the layout of the golf course, following in Maxwell’s every footstep. One day in early February 1935, the pair were staking off a routing for the 12th hole. Maxwell originally marked the 12th green on the high side of the creek, near the present-day 13th tee. Don leveled off some ground on the approach and whacked a ball that never even sniffed the proposed putting surface. In frustration, Old Rooster asked Maxwell, “Why don’t you put the green down there behind the creek?”

Maxwell studied the potential location for a moment and exclaimed, “Why didn’t I see that before?!”

It was this exchange that led to the creation of one of the greatest par fours in golf.

The iconic 12th green in preparation of the 2022 PGA Championship.

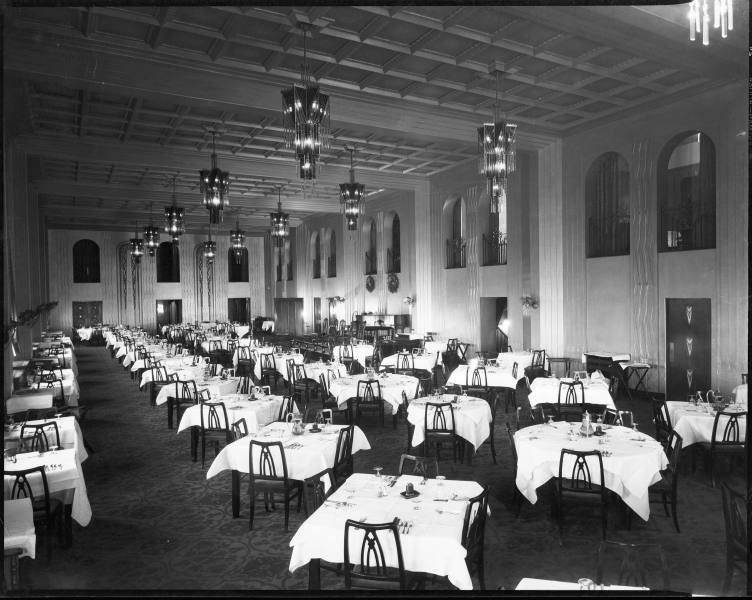

Otis McClintock was tabbed as chair of the clubhouse committee. This was one of the most important roles in the club’s early days, as the clubhouse would provide a central location by which the club’s other activities revolved. To stay afloat, the plan was to open the clubhouse first on the location that Maxwell had stipulated two years before. With this in mind, they were able to open preliminary facilities like the swimming pool, polo field, tennis courts, skeet range and more. These amenities allowed the club to continue collecting dues while the golf course was being finalized.

McClintock had an idea for who would design and construct the clubhouse. A few years earlier in 1932, he was on the hunt for an architect to build his own home. He sought out the recommendation of Waite Phillips, who had recently commissioned E.B. Delk to design “Villa Philbrook,” a 72-room Italian Renaissance mansion. Phillips’ connection with Delk ran deep – the Kansas City-based architect also designed Villa Philmonte on his ranch in New Mexico and the Philtower, his office building downtown.

But when McClintock approached Phillips fully expecting a resounding recommendation for Delk, Phillips said, “I’m going to help you with the selection, for one of the mistakes that I made was that Villa Philbrook is a palace and not a home.”

Ultimately, with the help of Phillips’ guiding hand, he selected two architects – John Duncan Forsyth and Donald McCormick. In 1928, Forsyth had designed the enormous 43,561-square-foot Marland Mansion in Ponca City. McCormick had just completed work on Cascia Hall Preparatory School, not far from Villa Philbrook.

Together, they designed McClintock’s 7,495-square-foot home atop a ridge on the corner of present-day 41st and Lewis. A French countryside design, the family painted the stone exterior a deep red before whitewashing it to expose a delicate shade of pink. The steeply-pitched roof was tiled with maroon shingles. McClintock was so pleased with his home that when he was tasked with finding architects for the Southern Hills clubhouse, he insisted on Forsyth and McCormick.

The McClintock Mansion in 1932. Photo courtesy of The Beryl Ford Collection/Rotary Club of Tulsa, Tulsa City-County Library and Tulsa Historical Society.

Similar to his French countryside home, plans were drawn up for a 17th Century English country clubhouse. The original building stood 12,000 square feet, and that original delicate pink hue that once donned the exterior of the McClintock Mansion has stood the test of time at Southern Hills.

Otis McClintock’s delicate pink can be found on the clubhouse and entrance gate at Southern Hills to this day.

The oil industry was as influential on Southern Hills Country Club as it was on any other organization or aspect of life in Tulsa in the first half of the 20th Century. The club’s first 11 presidents were professional oilmen. It wasn’t until the 12th president in 1948 that the club’s paramount elected position was held by someone outside the oil business.

That man was John M. Winters. A partner at local law firm Conner, Winters, Randolph and Ballaine, John Winters was a founding member of the club. And while he wasn’t directly involved in the oil business, even he couldn’t escape the industry’s influence. Through the Depression, Winters served as lead counsel for many of the city’s prominent oilmen. He was even on the board of directors of Waite Phillips’ First National Bank.

Winters’ impact at Southern Hills and golf’s governing bodies would impact the game for decades. He was fundamental in bringing the U.S. Open to Tulsa in 1958. He served as president of the United States Golf Association in 1962-63 and led the committee that negotiated with the Royal and Ancient Golf Club to unify the rules of golf. He was a member of the R&A, Cypress Point Club and Augusta National Golf Club, where he would personally present the Green Jacket to The Masters Tournament champion on five occasions.

The John Winters Bridge on the 12th hole at Southern Hills Country Club.

Winters was unexpectedly thrust into the spotlight at the 1968 Masters Tournament. When would-be champion Roberto Di Vicenzo signed an incorrect scorecard, he was disqualified from the tournament - giving the Green Jacket to Bob Goalby. Bob Jones, who typically presided over the Green Jacket ceremony at Butler Cabin was feeling ill, so he asked Clifford Roberts and Winters to take over those duties. It was Winters who had to explain the ruling to the world. To make matters worse, it was Di Vicenzo’s birthday.

John Winters explains the ruling against Roberto Di Vicenzo, awarding Bob Goalby the title of 1968 Masters Champion at the Green Jacket ceremony inside Butler Cabin. Starting at the 1:06:45 mark of the final round broadcast.

Even today, Winters’ legacy lives on. His son, Otis Winters, is one of Southern Hills’ longest-standing members. At the club’s first large-scale tournament, the 1946 Women’s Amateur, Otis served as a forecaddie on the seventh hole for eventual champion Babe Zaharias. It was the same year he won the club’s junior championship. In the 76 years since, he has volunteered at nearly every major championship the club has hosted, most recently at the 2022 PGA Championship.

It's because of the tireless efforts of these men who allowed Southern Hills to thrive in those early days. And there have undoubtedly been dozens of members through the decades who have left an indelible impact on Southern Hills Country Club.

While most played more golf, had more dinners and were more involved, none impacted the club more than Waite Phillips. It was his generous offer back on December 26, 1934 – and his strict set of obligations to fulfill it – that set Southern Hills Country Club up for a lifetime of success.

Tulsa Today

Many of the central figures in this story made their mark through the years, whether it was building golf courses or extravagant homes and offices. Here’s an update on a few of these locations.

Tulsa Country Club

Tulsa Country Club in 1929. Photo courtesy of The Beryl Ford Collection/Rotary Club of Tulsa, Tulsa City-County Library and Tulsa Historical Society.

Details are foggy in the years following the failed merger between TCC and the Tulsa Club. Dr. Kennedy would pass away in 1941, but the club remained private and would go on to flourish on the northwest side of downtown in spite of the Great Depression and the accidental shooting of a caddie by the club’s nightwatchman. In the decades since, TCC has hosted NCAA championships, Women’s Amateurs, senior championships and LPGA events. The club celebrated its 100-year anniversary in 2008 and Rees Jones completed a $6 million renovation in 2011.

Tulsa Club

R. Otis McClintock, one of the integral figures in this story, founded the Tulsa Club with three other businessmen in 1923. They first met in a boarding house across from the original Central High School, then in the basement of the Kennedy Building (built and owned by Dr. Kennedy). The Tulsa Club building was designed by renowned architect Bruce Goff and constructed at East 5th Street and South Cincinnati Avenue in downtown Tulsa in 1927, where it served as the home of both the Tulsa Club and Tulsa Chamber of Commerce for decades. The Tulsa Club ceased to exist in 1994 and the building fell into disrepair. The building was saved by investors and today houses the luxurious Tulsa Club Hotel.

Kennedy Golf Club

The Perry Maxwell-designed Kennedy Golf Club was Tulsa’s first public golf course, established by Dr. Kennedy’s son, James A. Kennedy. James was a four-time winner of the Oklahoma State Amateur. Famous gangster Pretty Boy Floyd once held up a day laborer to change the tire on his sedan just outside the golf course. Kennedy Golf Club closed during World War II. The two aerial photos are taken in 1939 and 1943, respectively.

Philtower

Edward Buehler Delk designed the Philtower in 1927. Topping out at 323 feet, it stood as the tallest building in Oklahoma for two years. Waite Phillips made his office on the 21st floor of the building. Today, another Tulsa businessman offices in the space and spent more than $1 million to painstakingly restore the office to its former glory.

Villa Philbrook

A 72-room mansion also designed by E.B. Delk for Waite Phillips and his family. When it opened in 1927, they hosted a housewarming party for hundreds of friends. Will Rogers, who attended the event, said, “I’ve been to Buckingham Palace, but it hasn’t anything on Waite Phillips’ house.”

The Phillips lived in the residence for a little more than 10 years before giving it to the city of Tulsa to be used as a museum and art center.

Bole Home

The first financial backers of Southern Hills Country Club were pursued by Warren, Canary and the committee at a dinner party hosted by George Smedley Bole, an independent oil operator, at his home at 4133 S. Victor Court. Named Oakwold Mansion, the home boasts nine bedrooms, nine bathrooms and nearly 14,000-square feet of living space.

Parriott Home

Foss Parriott, the first elected president of the club, hosted early meetings at his home in the historic Forest Hills neighborhood near 31st and Lewis. Built in a Colonial Revivalist style, the home features nine bedrooms, 11 bathrooms and nearly 13,000-square feet of living space.

McClintock Home

The 1931 French countryside estate designed by John Forsyth and Donald McCormick. The home included unique features, like an art-deco false fireplace with a built-in radio and a downstairs club room reminiscent of an old English pub. The home offers 7,500-square feet of living space. The delicate pink-hued exterior was sadly lost in the following days, but has since been painstakingly restored.

The Oklahoma Kid

The travels and triumphs of Bryan Karns, championship director for the 2022 PGA Championship.

On a warm, sunny day late last May, Bryan Karns sauntered over to a gaggle of reporters standing atop a small bluff in front of a field of American flags. They were there to speak with Lt. Col. Dan Rooney – founder of Folds of Honor – who was soon arriving to announce a partnership with PGA HOPE.

While they waited, they found a young championship director who spends his career behind the scenes, yet has a knack for stealing the show. He answered on-the-record questions in a casual, off-the-record sort of way. He didn’t hesitate or glance over to a publicist behind the lenses of his Ray-Ban Wayfarers. He gave time to each journalist, giving the scrum a one-on-one feel. And when the media time was done, he disappeared on his golf cart – presumably off to court another group of dignitaries somewhere on this 320-acre palace he calls home.

You see, here’s the thing about people who hold the title of “Championship Director” for the PGA of America. These are the guys and girls who have the golden ticket - a conspicuous “All-Access” logo on their credentials, sporting hats and shirts that you’ll never find in a souvenir shop and jetting around world-class courses in their topless Club Cars while the golf world graciously takes in the fruits of their labor. They’re golf royalty when it comes to the PGA Championship and the Ryder Cup.

It sounds badass – and much of it is – but there’s another side to this job you need to know about. What that All-Access badge or the media recognition or the rubbing of elbows with some of the most powerful people in golf don’t reveal is the tireless (and often tiresome) work they put in over the last two years and beyond. They don’t show the double-wide trailer they call an office tucked away in the back corner of some of the most coveted acreage in the country. And they don’t offer a glimpse into the scheduled moves across the country every two years to start over and do it all again.

That's why here and now, Bryan Karns is the luckiest man in the world.

You see, Bryan is an Oklahoma kid. Diplomas from Stillwater High School and Oklahoma State University hang on his wall. His wife is an Owasso Ram. And for someone who’s spent an entire career moving his family to Chicago and Washington D.C. and Louisville (twice) and Rochester, New York and French Lick, Indiana, it’s nice to be back home.

Golf wasn’t necessarily in the stars for Bryan growing up. He did play junior golf at Stillwater Country Club, a 1966 Donald Sechrest design. In 1994, his dad brought him to Southern Hills for the 76th PGA Championship.

“That was a pretty seminal moment for me growing up,” Karns said.

His closest connection to the game growing up came from his uncle, Lynn Blevins. Coming from a generations-deep Oklahoma State family, Blevins was the oddball – signing with the University of Oklahoma to play golf. That set up a career in the game – first coaching, then managing golf courses, then coaching again. His stops have included Regis University, Rogers State University, the University of Florida, the University of Iowa and his very first job – coaching his alma mater for three seasons beginning in 1979.

“He’s always been a PGA professional so it’s cool for me to have always had a connection to an actual PGA pro.”

But Karns was never good enough to play competitively (his words). An amateur sportsman in his younger years, golf just wasn’t a natural fit. When he enrolled at Oklahoma State University, though, he knew a career in athletics was calling his name. At the time, the school didn’t offer a sports management or sports media program, so Bryan studied the next best thing – journalism.

“My first real experience working in sports was as a sophomore at OSU. I had a deal with a couple of local papers. When their teams would come play in Stillwater, they would call me and I’d go out to take a few photos and write a recap for them.”

That initial experience led to a position with the university’s century-old newspaper, The Daily O’Collegian. Whatever high he was riding from seeing his byline in the school paper, it was swiftly and certainly squashed with his first assignment.

“I started out on the beat for Mike Gundy’s first spring and first season as head football coach. And that was a nightmare season. As much as I was a homer, it became increasingly difficult to write objective storylines.”

(In 2005, Oklahoma State finished dead last in the Big 12 Southern Division and suffered seven defeats in their last eight games, including a loss to the Texas Longhorns after leading the eventual national champions 28-12 at halftime.)

“It’s such a cool thing to me though,” Karns remarked. “If you’re an O’Colly writer, the access you get and confidence you get for being able to walk into a press room or go up to an athlete or coach and ask questions – that’s huge.”

His time with the Daily O’Collegian led into a position as a student sports information director for the OSU Athletics media relations office. It was here that Bryan seriously began considering career opportunities in sports.

“As a student SID in the summertime, there’s not much to do and I was looking to add to my résumé, so I found an internship posting outside of the Classroom Building on campus advertising a hospitality internship with the PGA of America.”

By this time, it was 2007 and the PGA Championship was scheduled to be back at Southern Hills.

“Part of what was so incredible about ’07 was you’ve got Tiger winning and the energy and the atmosphere was just unreal. You know, whoever is going to win is great, but Tiger is just different. When Tiger is associated with your club, it just means a little bit more. When he won, somehow I ended up in the ballroom when he was doing his Champions Toast and that was when I knew that I needed to keep doing this.”

When he went back to Stillwater that fall, he knew he wanted to stay in touch. He worked his way into a year-long gig at the 2008 Ryder Cup at Valhalla, where a rag-tag bunch of Americans (J.B. Holmes, Kenny Perry and Anthony Kim, anyone?) pulled off a miracle over a world-class European team.

Following that eye-opening experience in Louisville, he returned home once more to finish his master’s degree at Oklahoma State before taking a job with the Tulsa Shock – the WNBA franchise relocated from Detroit. With legendary head coach Nolan Richardson at the helm and Olympic gold medalist sprinter former UNC Tarheel point guard Marion Jones coming off the bench, the Shock won six games in their first season…out of 34.

“That’s a great talking point when you’re talking to people from Tulsa. They’re like, ‘you remember the Shock?!’ It was a grind but it showed me here’s one extreme and then there’s the other when it comes to job satisfaction. I remember when I interviewed to get back with the PGA, the guy that hired me said, ‘If you can sell that product in Tulsa, you can probably sell anything.’”

During the second half of 2010, Bryan was hired on to work the 2012 Ryder Cup. Following the American team’s meltdown at Medinah, he returned to Louisville to begin working on the 2014 PGA Championship in a corporate hospitality/marketing role. It was on the grounds of Valhalla Golf Club that he decided to work toward becoming a championship director.

“If you go and talk to most people on our staff, their goal professionally is to become a champ director. And they come from all different backgrounds. You have to be willing to be out in front and speak publicly. Not everyone is totally wired for it, but that’s the goal.”

After a year of selling corporate hospitality, the PGA of America signed a deal with French Lick Resort in Indiana to host the 2015 Senior PGA Championship. Louisville was the closest market to the resort and the team had done so well selling out Valhalla that Karns got his shot. He successfully operated the event in a town of 1,500 people and earned the same role for the 2017 Senior PGA Championship at Trump National Golf Club in Washington D.C.

“Both of those events were totally different for several reasons, but both were great because it prepared me for so many things. In the spring of 2017, I was kind of at a crossroads. Once you get into the champ director role, you say ‘alright I’m happy to do a Senior PGA, but now I want to do a PGA.”

The timing for Karns couldn’t have been better. A week after Bernhard Langer squeaked past Vijay Singh at Trump National, the PGA of America announced that Southern Hills Country Club would host the 2021 Senior PGA Championship and a PGA Championship at some point by 2030.

“That really kind of served as a boost to me because I knew that I was going to be able to come home in a few years, and in the meantime, we got to go to Oak Hill in 2019. Rochester and Oak Hill are fantastic. One of the best memberships I’ve ever been around.”

After a successful two-year stint in New York, the Karns family packed up and moved home. Little did they know what was to come.

The Karns family packed up and returned to Oklahoma - and Southern Hills Country Club - after the 2019 Senior PGA Championship.

Tulsa was hoping for a PGA Championship sooner rather than later. When the 2021 Senior PGA was announced, the governing body also promised a PGA Championship by 2030. Karns, who had moved his family to Tulsa to start work on 2021, was realistic about Tulsa’s chances.

“I know everyone here wanted it to be as soon as possible, but everything was pointing toward 2030,” Karns said.

He arrived in Green Country with the PGA of America constituency for their customary initial site visit for the Senior PGA Championship in 2018. They met with Southern Hills general manager Nick Sidorakis, staff and members of the club to discuss logistics and planning. By the end of the visit, the championship team was able to put together a preliminary corporate budget. Southern Hills was so excited that Sidorakis mentioned the possibility of going on sale before the end of 2018.

“I said, ‘Nick, it’s way to early. It’s like, so early it’s absurd,’” Karns said.

The issue is hyping the event too soon and losing your leverage with the community before the event actually happens. Sidorakis asked Karns to trust him, though.

“I told him, ‘Nick, if you can line up ten meetings, I’ll come back down there.”

In a week, Sidorakis had a full itinerary for Karns. Ten meetings later, they had sold seven chalets and three suites.

“That never happens,” Karns said. “We had such tremendous corporate momentum.”

Over the course of the next year, it looked like Southern Hills was primed for one of the most successful events in senior golf major championship history. Then the world stopped.

There’s not much more to write about COVID-19 that hasn’t already been written. We remember the details vividly. On March 11, 2020 NBA superstar Rudy Gobert tested positive for COVID-19. Within minutes, his team’s game against the Oklahoma City Thunder was postponed.

Within days, the entire world was shut down.

Planet earth was living in a scene from Contagion.

No one knew what was happening. No one knew if they were safe. No one knew if life would ever be the same.

The PGA Tour Champions shut down for five months. The 2020 Senior PGA Championship – scheduled for May of 2020 in Benton Harbor, Michigan – was canceled. Even into the first weeks of 2021, Karns and his team were scrambling in Tulsa.

“We got to January and were thinking this is brutal because everything we wanted to do from a tent standpoint, the City of Tulsa Health Department wouldn’t sign off on it,” Karns said. “There were also companies who were saying they couldn’t invite people because of their new corporate entertainment policies.”

Then January 6 happened. Call it what you want – we’re not here to get political – but there was an immediate backlash on properties owned by the former POTUS. Within 96 hours, the PGA of America announced that the 2022 PGA Championship would not be played at Trump National Golf Club Bedminster in New Jersey. And that’s when Karns really got to work.

“The first moment (it was announced), I picked up the phone and called Nick (Sidorakis),” Karns said. “Here’s this perfect pivot. We can go to all these companies that have committed a record amount for the Senior PGA Championship and say, ‘if we were able to get the PGA Championship, would you commit?’ This would allow us to move a lot of hospitality to 2022 and give us an opportunity to offer some hospitality at the Senior PGA in the form of open-air structures and things like that. And within 48 hours we had enough commitments that when the potential venues were being evaluated, it was a no-brainer.”

By the end of the month, we would know the fate of the 2022 PGA Championship. Before Tiger’s wreck; before Phil’s triumph at The Ocean Course and subsequent self-imposed downfall a handful of months later, Southern Hills was once again in the spotlight of the golf world.

Karns shows off the Wanamaker Trophy during a football game at his alma mater, Oklahoma State University.

In the 14 months since that announcement, Karns and his team have pulled off the unthinkable. They successfully completed a Senior PGA Championship amid a throng of health and safety hurdles thrown their way. They planned an event in less than a year and a half that will bring in more than $140 million economically to the City of Tulsa. And they played the storylines to perfection.

Will Tiger return to the site of his 2007 PGA Championship victory? Will Phil defend his Wanamaker Trophy as the oldest PGA Champion in history? Will one of the Oklahoma boys shock the world and win in their home state?

However it plays out, you know Karns will be somewhere out there living his dream with a pair of Wayfarers and a soft smile on his face. Because no matter how many people show up or who holds the Wanamaker on Sunday evening, he knows that he’s home.

“You go to a lot of places out there and people are like, ‘yeah that’s my hometown, but I don’t get back much.’ I grew up in Stillwater. I went to Oklahoma State. For me, being able to take this and help grow that brand of being Oklahoman – that’s special to me.”

Karns celebrates with his wife, Ashlie, after a United States victory in the 2020 Ryder Cup.

The Baron of Bartlesville

Frank Phillips never set a course record, but his influence has no doubt influenced the game of golf along the banks of the Caney River.

On a bluff above a small lake in far eastern Osage County, a simple structure built from native rock is cut from the hillside. Quaint and unassuming, it’s not until the thick bronze door swings open that one realizes the opulence and once-lavish taste of those who permanently reside there. The 12-inch-thick steel-reinforced walls are adorned with thousands of colorful mosaic tiles. Columns of Italian marble rise to the ceiling. This is the final resting place of Frank Phillips, a serial entrepreneur and the subject of this story.

By trade, he was identified by many titles. Barber. Banker. Oil Baron. By interest, he was a conservationist, an aviation enthusiast and a civil servant. But it was the names given to him by others – “Wah-Sha-She Hluah-Ke-He-Kah” by the Osage and “Uncle Frank” by the community – that he chose to be remembered by.

Much has been told about the life and legacy of Frank Phillips in Oklahoma. About his early employment as a barber, first in Iowa, then Aspen, then Ogden. About his rise to power drilling black gold out of the Osage hills. About his partnership with brothers L.E. and Waite on various enterprises. About the legendary Phillips Ranch southwest of town, a 17,000-acre domain filled with exotic species from every corner of the earth.

Our story begins not with the rise, but in the prime of Phillips’ wealth and influence.

As the earliest days of oil boomed and Bartlesville swelled, the need for recreation in the area became apparent. The first mentions of a country club came in early 1908, when E.F. Blaise formed a committee of interested parties. Judge J.J. Shea was appointed to organize the club, with stock dues valued at $100 per share. On December 11, 1908, the Bartlesville Country Club was incorporated, with plans to lay out golf links the following year. Frank Phillips was elected as an inaugural officer of the club. Almost immediately, however, the club ran into roadblocks. By March of 1910, the officers and membership had still not settled on a permanent home. This matter would linger another year before firm plans were decided on.

It wasn’t until March of 1911 that L.E. Phillips claimed, “I have found the most available spot in the country for a country club.” Upon his suggestion and the approval of the club’s officers, plans for the first golf course in Bartlesville were laid. An organization comprised of stockholding members purchased a parcel of land from Pawhuska’s Paul Mason. The allotment was three-quarters of a mile west of the Osage / Washington County border line, on the Pawhuska Road (present-day Frank Phillips Boulevard). The site was “just beyond the mound,” near the present-day Bartlesville Municipal Airport. The club, which hired the services of Scottish-born George C. Fernie of Independence Country Club to lay out the course. L.E. served on the club’s original Board of Directors and was charged with traveling to Kansas City to gather ideas for the construction of a clubhouse. When bids for the construction were reviewed, the contract was awarded to local firm Hatcher and Moffet at the price of $4,200. On Wednesday, Nov. 29, 1911, the game of golf in Bartlesville was born. Invitations to the opening ceremonies were sent to delegates as far as Muskogee and Independence, Kansas. In preparation of the festivities, the Morning Examiner noted, “The ground (is) shaved, shampooed and manicured, so to speak, and a golf expert has laid out the links which have been pronounced by those who know to be the most perfect and complete in the entire southwest.”

Original members of Bartlesville Country Club included Huntington B. Henry of Henry Oil and Gas Company, Henry Vernon Foster of the Indian Territory Illuminating Oil Company, attorney John H. Kane, judge J.J. Shea and of course, the three Phillips brothers – Frank, L.E. and Waite.

Original Bartlesville CC

This original nine-hole, par 35 track featured one water hazard off the first hole and five mounded bunkers (some with sand in them). As it was outside city limits, Judge Shea offered his car as public transportation to the club.

The honeymoon between the club and its members was short, however. Less than five months following the grand celebration, the club required $20,000 in improvements to the grounds, golf course, clubhouse and furnishings. What took less than $5,000 to create now ballooned in cost. By the summer of 1912, William Brown, another Scot, had been hired to take over as the club professional. Golf course maintenance was by committee, and the membership added bunkers on the seventh and ninth holes. The track stretched to 3,100 yards and the greens were covered with “well-oiled sand.”

The next few years proved rocky for Bartlesville’s first club. As it was outside city limits, the site demonstrated to be significant effort visit on a nice day, and nearly impossible with rain or other inclement weather in the forecast. Financial concerns of upkeep mounted, and membership began to hemorrhage. By June of 1915, what remained of the membership began discussions of moving the club to a more appropriate and accessible site near Tuxedo Park. Instead, it was decided that the Bartlesville Interurban Railway would run a route out to the site of the club and it would be reorganized as the Oak Hill Club. Frank, as an elected member of the Interurban’s board of directors, was integral in the establishment of this line.

It was also during this time that Frank began to show interest and leadership in the club. When a committee representing Henry Latham Doherty’s Cities Service Company – which would later become the Citgo Corporation – visited town, a luncheon in their honor was to be held at the club. When inclement weather washed out their plans, Frank offered his home on Cherokee Avenue to host the event on short notice. Doherty’s representatives were impressed that one could host nearly 70 men on short notice without importing so much as a single piece of silverware.

By the early 1920s, the road to the club had once again fallen in disrepair, but Oak Hill was thriving. Local newspapers were filled with notices of dinner parties and other fine affairs at the club. Ed Dudley had taken over at Oak Hill as head professional, coming from a similar position at Miami, Oklahoma’s Rockdale Country Club. He would spend three or four years in Bartlesville, marrying the daughter of Mr. and Mrs. W.F. Johnson before becoming the head professional at Pawhuska Country Club. Dudley would go on to have a successful career in golf, winning the Oklahoma Open twice, finishing his career with 11 Top-10 finishes in major championships and boasting a 3-1 record in Ryder Cup matches. Off the course, he would accept a position to be the head professional at Oklahoma City Golf and Country Club before answering the call to be the first professional at Bobby Jones’ Augusta National Golf Club in 1932, a position he would hold until 1957.

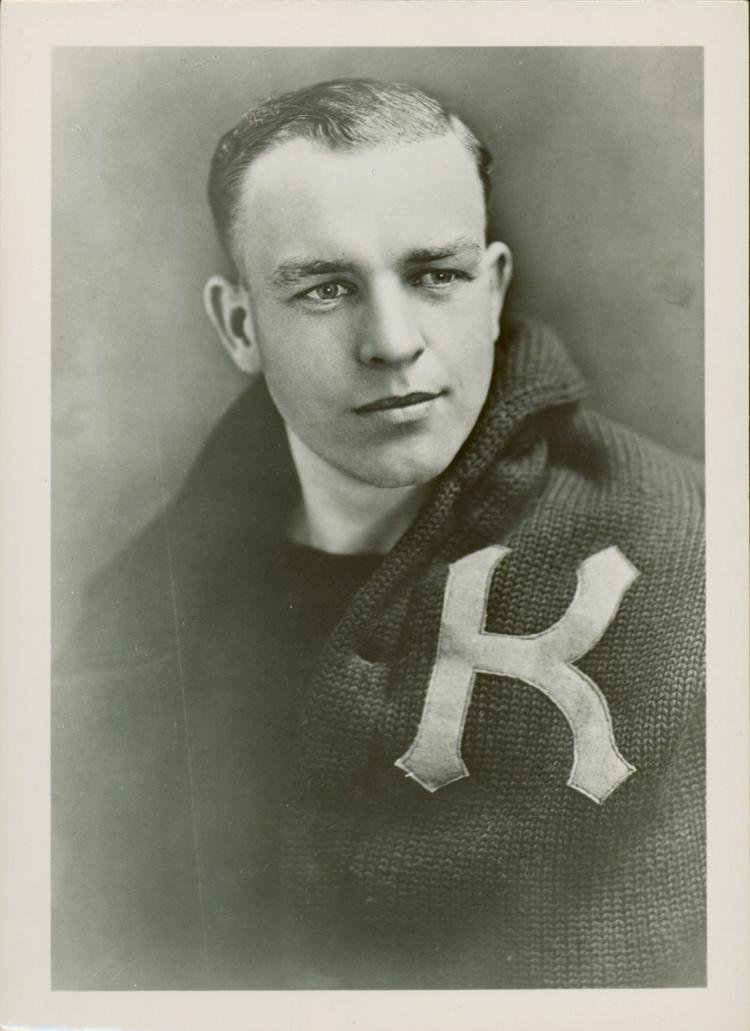

Ed Dudley and Bobby Jones

But despite the dinner parties and nine-hole amusement that Oak Hill provided on the other side of The Mound, a small group of influential men in town believed Bartlesville was ready for a more refined establishment. Frank and H.V. Foster, both members of the original club, put their best men on it. For Frank, that meant tabbing Paul Endacott for the project. Paul was born in Oklahoma but grew up in Lawrence, Kansas. As a child, he spent time at the local YMCA learning the game of basketball from Dr. James Naismith. He would go on to play for Phog Allen at the University of Kansas, leading his team to two national championships and earning national player of the year honors. As a student at K.U., he heard L.E. Phillips speak at a banquet and he decided to pursue a career with Phillips Petroleum. After graduation, he moved to Bartlesville and began a career that would see him move up the ranks in the organization, eventually to president and chairman. But before that, Paul was tasked with finding prospective land for a new country club. When he returned to Frank, he reported on a parcel south of town hugging the opposite bank of the Caney River, surrounding the Silver Lake Delaware Indian cemetery.

Paul Endacott

By this time, Frank’s only son – John Gibson Phillips – had established himself as one of the young executive socialites of the town. With the Roaring Twenties raging across America’s high society and Bartlesville choc full of oil-rich families, a new social class of young, raffish men emerged. In Bartlesville, the “Halcyon Club” was established. This association, with John G. Phillips in the middle of the pack, enforced what was happening on the local social calendar, and who was included. If it was a new country club they wanted, it was a new country club they would get.

This spoiled egotism was always a point of contention between Frank and his son. From his earliest days in Bartlesville, John grew accustomed to Frank showering him with lavish gifts in an attempt to make up for his countless hours working. It was customary for Frank, as the head of the most popular bank in town and no less than 15 other corporations, to work 18-hour days. In his formidable years, John developed a thirst for the bottle and an intense craving to stay in the spotlight. This led Frank to many sleepless nights, frustrated with the antics of the younger Phillips.