The Entirely Unlikely (But True) Story of Southern Hills Country Club

“The only things we keep permanently are those we give away.” – Waite Phillips

Early sketch of SHCC by Paul Corrubia

Waite Phillips wasn’t about to fork over his money to the two businessmen who approached him about financing a new country club in Tulsa.

This was the Great Depression, after all.

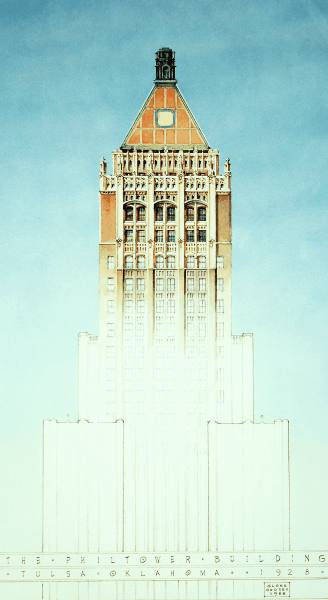

The oilman-turned-banker had already made a name as one of the wealthiest men in Tulsa and - for that matter - all of America. His endeavors alongside brothers Frank and L.E. to build Phillips Petroleum Company before going about it on his own had made him millions, and his impression on the city was everywhere. From his downtown office buildings (aptly named the Philtower and Philcade) to his 72-room Italian Renaissance-style mansion near 31st and Peoria, Waite Phillips had already made his mark on the city.

He arrived in Oklahoma in 1911 at his brothers’ behest. Frank and L.E. had been risking everything for eight years in Bartlesville territory at this point. They drilled their first gusher, the Anna Anderson (named after the eight-year-old Delaware Indian girl who held the land lease) in 1905 and organized the largest bank in town, Citizens’ Bank and Trust, to offset the volatility of their drilling ventures. The Phillips family struck it rich, and Waite wanted his own piece of the pie.

His time in Bartlesville lasted just four years before Waite set out on his own. Moving to Tulsa, he began a career as an individual oil producer. A decade later, he sold most of his holdings to the Barnsdall Oil Company for $25 million.

While he was driven to succeed in his career, his passion was for the land. In 1929, he acquired 770 acres south of Tulsa to be utilized for family recreation and horseback riding. The spread, historically a part of the Creek Nation, covered section 32-19N-13E and section 5-18N-13E along present-day 61st Street and Lewis Avenue. This plot featured dramatic land movement, rising more than 150 feet in elevation in the southeast corner and falling away toward the Arkansas River. A meandering tributary center-cut the property, delivering rich nutrients to the soil beneath.

It was prime real estate at a time when real estate wasn’t prime.

Waite Phillips with his wife - Genevieve - and children - Elliott and Helen Jane at Villa Philbrook.

In 1934, Tulsa businessmen William (Bill) K. Warren and Cecil Canary were two disgruntled members of Tulsa Country Club, an A.W. Tillinghast design northwest of downtown located on the property of prominent Tulsan Dr. S.G. Kennedy. The grip of the Depression had taken hold across the country, and while some Tulsans were insulated to the majority of its effects due to their oil holdings, it was being felt strongly in banking and land ownership. That was the case with Kennedy, who was rumored to announce in the fall of 1934 that once the club’s latest lease on the land expired in 1936, he planned to sell the property.

This would have been a disaster for the club’s current members. What was once a safe haven for Tulsa’s societal highbrow was now on the brink of being shuttered - or worse - flooded by hackers, duffers and ruffians. More speculation arose when members of the Hy Hat Club (Tulsa’s equivalent of the legendary Halcyon Society in Bartlesville, of which Waite’s nephew was a member) began showing up dead on the streets of Tulsa’s posh neighborhoods. Phil Kennamer – the son of a federal judge – was charged with the slaying of John Gorrell – the son of a prominent Tulsa doctor. Kennamer fired two rounds into the back of Gorrell’s head at the intersection of South Victor Avenue and East Forest Boulevard, just a few hundred yards from Waite Phillips’ home, Villa Philbrook. Days later, Sidney Born – the president of the Hy Hat Club and the individual who drove Kennamer to the eventual murder scene – was found dead of an apparent suicide.

Tulsa’s upper echelon was in a panic. One reporter noted, “Have Tulsa’s young been destroyed by their own indulgences? Are they sated and aged before their time? Have they seen and done everything while still in their teens so they must seek in shadowy places for new thrills?”

The same article reported that “one exclusive club for adults sent out a confidential letter to its members asking if they wished to sponsor a series of planned – and supervised – entertainments for Tulsa’s young.”

Those who socialized at the Tulsa Club downtown and golfed at Tulsa Country Club saw a potential opportunity. They formed a plan to merge the two clubs and expand the footprint to include Kennedy Golf Course, a 1925 Perry Maxwell-designed public course adjacent to Tulsa Country Club. This would give members the opportunity to expand their family-friendly activities, including polo, tennis and swimming.

While the group appointed Warren to negotiate a workaround with Kennedy, they made it clear that they weren’t above looking at alternative options. On Dec. 4, 1934, Warren wrote a letter to Phillips, boldly asking the banker to finance a new facility on behalf of the “Tulsa Town and Country Club.” The Kennedy deal nearly happened, but at the last minute for reasons lost to time, the merger fell through and members were left scrambling for other options.

An announcement in The Oklahoma News on December 24, 1934.

Warren knew of Waite Phillips’ property south of town. He knew it was premium land, ideally suited for activities of the day. On Dec. 26, 1934 – two days after it was reported that the Tulsa Country Club would vote on a merger with the Tulsa Club, Phillips summoned Warren to his office to discuss the alternative plan of building a new club on his property. Warren was nervous about facing Phillips alone, so he brought along Cecil Canary for moral reinforcement.

Tulsa businessmen R. Otis Mclintock, Cecil Canary and William K. Warren, Sr.

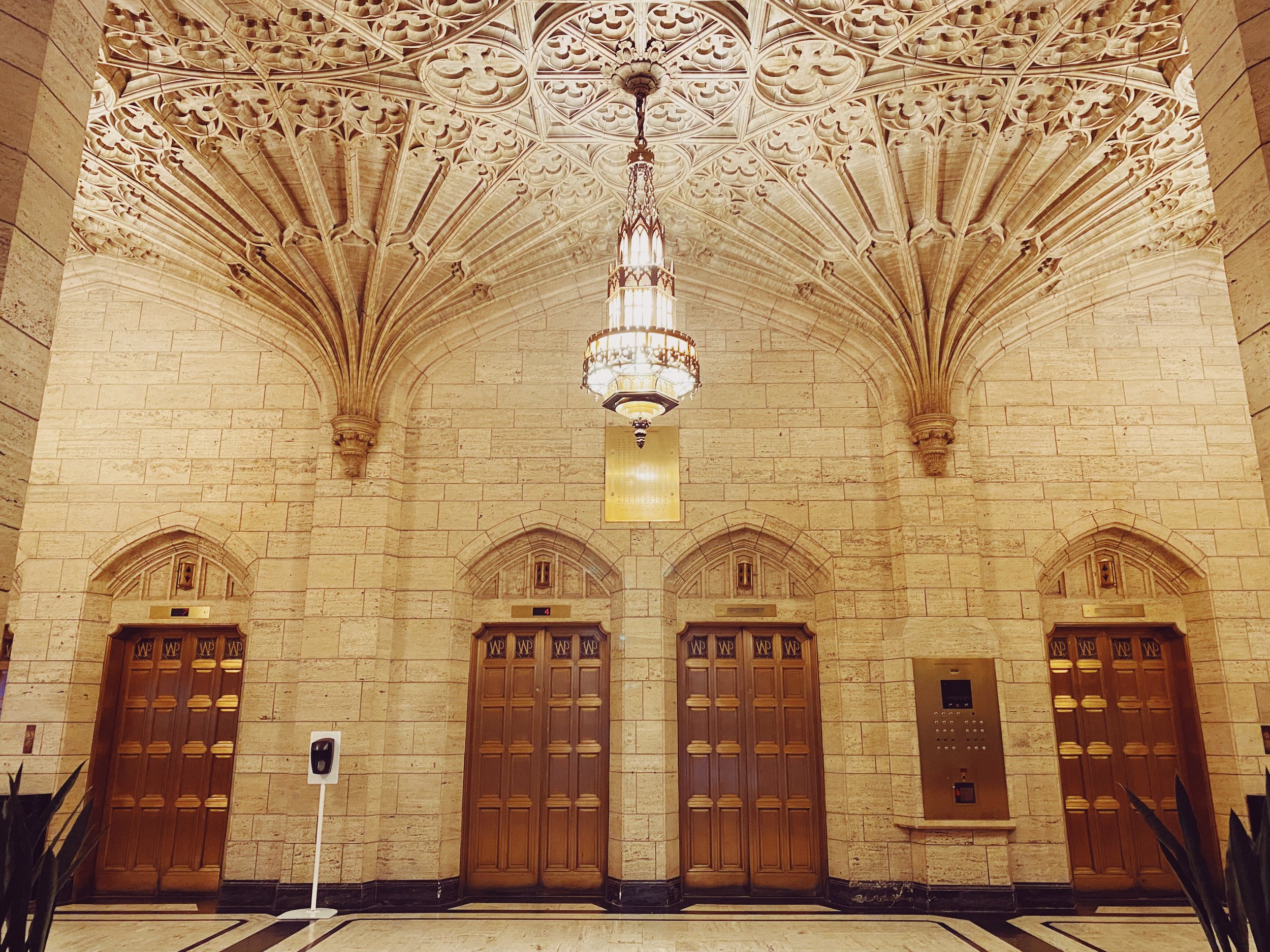

On the 21st floor of the Philtower – the E.B. Delk-designed gem of the Tulsa skyline, Warren and Canary stepped into Phillips’ cavernous office. A buffalo hide spread across the floor. Chandeliers hung from the arched ceiling. A blue-tiled fireplace lined the wall behind his desk, cluttered with a smattering of letters addressed to the banker and financier.

“Every paper you see here contains a request for money to help start a business venture or support a worthy cause,” Phillips started in on the men. “Not all of the business ventures are worthy of much consideration, Mr. Warren, but yours is ridiculous!”

Bill and Cecil were shocked at the response. Did he not believe in the family values that country clubs offered? Could he not see that Tulsa was starved for wholesome sporting activities? Just when they felt like jumping out the window to spare themselves any more embarrassment, Phillips softened his tone and entered negotiation mode.

“I have a counter-proposal. If your group will pledge to spend $150,000 in two years – one half to be spent the first year to construct the family-type country club you described in your letter, I will donate the three hundred acres you need. However, I will not put up one cent to help build the facilities.”

Warren and Canary left Waite Phillips’ office that day with a formal written offer from the oilman and banker, but little hope that they could actually fulfill his demands.

The letter provided more detail – by January 15, 1935, just 20 days after their meeting, they needed to have 150 commitments of $1,000 each. While both men were considered wealthy by the day’s standards, neither felt comfortable writing a $1,000 check. How they were going to find and convince 148 others to do the same in less than a month was beyond the realm of their imagination.

Another proviso in the letter was where the clubhouse was to be located on the grounds. It stated: “As part of this proposal I stipulate that the main clubhouse must be located approximately in the center of the south line of the acreage used for club purposes. This location was recommended as most desirable by Perry Maxwell when he made a preliminary survey a year or two ago.”

This is the first mention of Maxwell in relation to Southern Hills. It turns out Warren and Canary weren’t the first to approach Phillips with the possibility of building a golf course. In 1933, the golf course architect first proposed to Phillips links on the land. According to Maxwell’s second wife, “He had the rare ability to see a golf course nestled among scrub oaks. He did not like to disturb the land, and it was because he fell in love with this beautiful piece of property that he begged Waite Phillips to allow him to build a course on the land.”

At this point in his career, Maxwell was well-known as a golf course architect. Through his previous banking career in Ardmore, Oklahoma, he knew the Phillips family well. Nearly ten years prior, he designed Hillcrest Country Club in Bartlesville for Frank, L.E. and the prominent oil barons that made up the Halcyon Society. This connection, coupled with his propensity for sticking to a timeline and a budget, made him Waite’s choice for building the golfing grounds of Southern Hills Country Club…if it ever actually got off the ground.

If the project failed, it wouldn’t be for lack of trying. Warren and Canary immediately consulted with Otis McClintock and other interested members from the Tulsa Club and Tulsa Country Club. George Bole, another Tulsa oilman, hosted the first dinner party at his 14,000 square foot Oakwold Mansion catered by John Mayo of the Mayo Hotel.

One hundred and twenty-five prominent Tulsans attended the dinner party and the group elected the first board of governors for the club: Foss Parriott was elected president and S.C. Canary, Rush Greenslade and C.H. Lieb were vice presidents. Jack Padon was elected secretary-treasurer and directors included Bill Warren, Don C. Bothwell, Jack L. Shakely, C.W. Flint, Dudley Morgan and Otis McClintock.

When the dinner party ended, the club had 74 signed pledges…but just three were accompanied by $1,000 checks. All they needed at this point, though, was the signatures. These were the days when a handshake meant something, and they trusted the men who signed pledges to follow through.

By January 14, Bill Warren presented Phillips with a list of 140 men who pledged $1,000 each. Despite being 10 signatures short of their goal, Waite accepted the offer, knowing how difficult this task had been. When the new club was announced, Dr. Kennedy was so upset that he withdrew $600,000 from Phillips’ and McClintock’s First National Bank.

Meetings of the newly formed Southern Hills Country Club board of directors were held in three locations – the Tulsa Club at the corner of 5th and Cincinnati, Foss Parriott’s home near 31st and Lewis and Otis McClintock’s home on the corner of 41st and Lewis.

Don Bothwell, affectionately known to early club members as “Old Rooster,” was selected to be the golf course committee chair. It was he who ultimately tabbed Perry Maxwell to lay out the links – naturally with a nod from Phillips. Within days of the deed being handed over to the club, Maxwell was on-site. Old Rooster was intimately involved in the layout of the golf course, following in Maxwell’s every footstep. One day in early February 1935, the pair were staking off a routing for the 12th hole. Maxwell originally marked the 12th green on the high side of the creek, near the present-day 13th tee. Don leveled off some ground on the approach and whacked a ball that never even sniffed the proposed putting surface. In frustration, Old Rooster asked Maxwell, “Why don’t you put the green down there behind the creek?”

Maxwell studied the potential location for a moment and exclaimed, “Why didn’t I see that before?!”

It was this exchange that led to the creation of one of the greatest par fours in golf.

The iconic 12th green in preparation of the 2022 PGA Championship.

Otis McClintock was tabbed as chair of the clubhouse committee. This was one of the most important roles in the club’s early days, as the clubhouse would provide a central location by which the club’s other activities revolved. To stay afloat, the plan was to open the clubhouse first on the location that Maxwell had stipulated two years before. With this in mind, they were able to open preliminary facilities like the swimming pool, polo field, tennis courts, skeet range and more. These amenities allowed the club to continue collecting dues while the golf course was being finalized.

McClintock had an idea for who would design and construct the clubhouse. A few years earlier in 1932, he was on the hunt for an architect to build his own home. He sought out the recommendation of Waite Phillips, who had recently commissioned E.B. Delk to design “Villa Philbrook,” a 72-room Italian Renaissance mansion. Phillips’ connection with Delk ran deep – the Kansas City-based architect also designed Villa Philmonte on his ranch in New Mexico and the Philtower, his office building downtown.

But when McClintock approached Phillips fully expecting a resounding recommendation for Delk, Phillips said, “I’m going to help you with the selection, for one of the mistakes that I made was that Villa Philbrook is a palace and not a home.”

Ultimately, with the help of Phillips’ guiding hand, he selected two architects – John Duncan Forsyth and Donald McCormick. In 1928, Forsyth had designed the enormous 43,561-square-foot Marland Mansion in Ponca City. McCormick had just completed work on Cascia Hall Preparatory School, not far from Villa Philbrook.

Together, they designed McClintock’s 7,495-square-foot home atop a ridge on the corner of present-day 41st and Lewis. A French countryside design, the family painted the stone exterior a deep red before whitewashing it to expose a delicate shade of pink. The steeply-pitched roof was tiled with maroon shingles. McClintock was so pleased with his home that when he was tasked with finding architects for the Southern Hills clubhouse, he insisted on Forsyth and McCormick.

The McClintock Mansion in 1932. Photo courtesy of The Beryl Ford Collection/Rotary Club of Tulsa, Tulsa City-County Library and Tulsa Historical Society.

Similar to his French countryside home, plans were drawn up for a 17th Century English country clubhouse. The original building stood 12,000 square feet, and that original delicate pink hue that once donned the exterior of the McClintock Mansion has stood the test of time at Southern Hills.

Otis McClintock’s delicate pink can be found on the clubhouse and entrance gate at Southern Hills to this day.

The oil industry was as influential on Southern Hills Country Club as it was on any other organization or aspect of life in Tulsa in the first half of the 20th Century. The club’s first 11 presidents were professional oilmen. It wasn’t until the 12th president in 1948 that the club’s paramount elected position was held by someone outside the oil business.

That man was John M. Winters. A partner at local law firm Conner, Winters, Randolph and Ballaine, John Winters was a founding member of the club. And while he wasn’t directly involved in the oil business, even he couldn’t escape the industry’s influence. Through the Depression, Winters served as lead counsel for many of the city’s prominent oilmen. He was even on the board of directors of Waite Phillips’ First National Bank.

Winters’ impact at Southern Hills and golf’s governing bodies would impact the game for decades. He was fundamental in bringing the U.S. Open to Tulsa in 1958. He served as president of the United States Golf Association in 1962-63 and led the committee that negotiated with the Royal and Ancient Golf Club to unify the rules of golf. He was a member of the R&A, Cypress Point Club and Augusta National Golf Club, where he would personally present the Green Jacket to The Masters Tournament champion on five occasions.

The John Winters Bridge on the 12th hole at Southern Hills Country Club.

Winters was unexpectedly thrust into the spotlight at the 1968 Masters Tournament. When would-be champion Roberto Di Vicenzo signed an incorrect scorecard, he was disqualified from the tournament - giving the Green Jacket to Bob Goalby. Bob Jones, who typically presided over the Green Jacket ceremony at Butler Cabin was feeling ill, so he asked Clifford Roberts and Winters to take over those duties. It was Winters who had to explain the ruling to the world. To make matters worse, it was Di Vicenzo’s birthday.

John Winters explains the ruling against Roberto Di Vicenzo, awarding Bob Goalby the title of 1968 Masters Champion at the Green Jacket ceremony inside Butler Cabin. Starting at the 1:06:45 mark of the final round broadcast.

Even today, Winters’ legacy lives on. His son, Otis Winters, is one of Southern Hills’ longest-standing members. At the club’s first large-scale tournament, the 1946 Women’s Amateur, Otis served as a forecaddie on the seventh hole for eventual champion Babe Zaharias. It was the same year he won the club’s junior championship. In the 76 years since, he has volunteered at nearly every major championship the club has hosted, most recently at the 2022 PGA Championship.

It's because of the tireless efforts of these men who allowed Southern Hills to thrive in those early days. And there have undoubtedly been dozens of members through the decades who have left an indelible impact on Southern Hills Country Club.

While most played more golf, had more dinners and were more involved, none impacted the club more than Waite Phillips. It was his generous offer back on December 26, 1934 – and his strict set of obligations to fulfill it – that set Southern Hills Country Club up for a lifetime of success.

Tulsa Today

Many of the central figures in this story made their mark through the years, whether it was building golf courses or extravagant homes and offices. Here’s an update on a few of these locations.

Tulsa Country Club

Tulsa Country Club in 1929. Photo courtesy of The Beryl Ford Collection/Rotary Club of Tulsa, Tulsa City-County Library and Tulsa Historical Society.

Details are foggy in the years following the failed merger between TCC and the Tulsa Club. Dr. Kennedy would pass away in 1941, but the club remained private and would go on to flourish on the northwest side of downtown in spite of the Great Depression and the accidental shooting of a caddie by the club’s nightwatchman. In the decades since, TCC has hosted NCAA championships, Women’s Amateurs, senior championships and LPGA events. The club celebrated its 100-year anniversary in 2008 and Rees Jones completed a $6 million renovation in 2011.

Tulsa Club

R. Otis McClintock, one of the integral figures in this story, founded the Tulsa Club with three other businessmen in 1923. They first met in a boarding house across from the original Central High School, then in the basement of the Kennedy Building (built and owned by Dr. Kennedy). The Tulsa Club building was designed by renowned architect Bruce Goff and constructed at East 5th Street and South Cincinnati Avenue in downtown Tulsa in 1927, where it served as the home of both the Tulsa Club and Tulsa Chamber of Commerce for decades. The Tulsa Club ceased to exist in 1994 and the building fell into disrepair. The building was saved by investors and today houses the luxurious Tulsa Club Hotel.

Kennedy Golf Club

The Perry Maxwell-designed Kennedy Golf Club was Tulsa’s first public golf course, established by Dr. Kennedy’s son, James A. Kennedy. James was a four-time winner of the Oklahoma State Amateur. Famous gangster Pretty Boy Floyd once held up a day laborer to change the tire on his sedan just outside the golf course. Kennedy Golf Club closed during World War II. The two aerial photos are taken in 1939 and 1943, respectively.

Philtower

Edward Buehler Delk designed the Philtower in 1927. Topping out at 323 feet, it stood as the tallest building in Oklahoma for two years. Waite Phillips made his office on the 21st floor of the building. Today, another Tulsa businessman offices in the space and spent more than $1 million to painstakingly restore the office to its former glory.

Villa Philbrook

A 72-room mansion also designed by E.B. Delk for Waite Phillips and his family. When it opened in 1927, they hosted a housewarming party for hundreds of friends. Will Rogers, who attended the event, said, “I’ve been to Buckingham Palace, but it hasn’t anything on Waite Phillips’ house.”

The Phillips lived in the residence for a little more than 10 years before giving it to the city of Tulsa to be used as a museum and art center.

Bole Home

The first financial backers of Southern Hills Country Club were pursued by Warren, Canary and the committee at a dinner party hosted by George Smedley Bole, an independent oil operator, at his home at 4133 S. Victor Court. Named Oakwold Mansion, the home boasts nine bedrooms, nine bathrooms and nearly 14,000-square feet of living space.

Parriott Home

Foss Parriott, the first elected president of the club, hosted early meetings at his home in the historic Forest Hills neighborhood near 31st and Lewis. Built in a Colonial Revivalist style, the home features nine bedrooms, 11 bathrooms and nearly 13,000-square feet of living space.

McClintock Home

The 1931 French countryside estate designed by John Forsyth and Donald McCormick. The home included unique features, like an art-deco false fireplace with a built-in radio and a downstairs club room reminiscent of an old English pub. The home offers 7,500-square feet of living space. The delicate pink-hued exterior was sadly lost in the following days, but has since been painstakingly restored.