The Baron of Bartlesville

On a bluff above a small lake in far eastern Osage County, a simple structure built from native rock is cut from the hillside. Quaint and unassuming, it’s not until the thick bronze door swings open that one realizes the opulence and once-lavish taste of those who permanently reside there. The 12-inch-thick steel-reinforced walls are adorned with thousands of colorful mosaic tiles. Columns of Italian marble rise to the ceiling. This is the final resting place of Frank Phillips, a serial entrepreneur and the subject of this story.

By trade, he was identified by many titles. Barber. Banker. Oil Baron. By interest, he was a conservationist, an aviation enthusiast and a civil servant. But it was the names given to him by others – “Wah-Sha-She Hluah-Ke-He-Kah” by the Osage and “Uncle Frank” by the community – that he chose to be remembered by.

Much has been told about the life and legacy of Frank Phillips in Oklahoma. About his early employment as a barber, first in Iowa, then Aspen, then Ogden. About his rise to power drilling black gold out of the Osage hills. About his partnership with brothers L.E. and Waite on various enterprises. About the legendary Phillips Ranch southwest of town, a 17,000-acre domain filled with exotic species from every corner of the earth.

Our story begins not with the rise, but in the prime of Phillips’ wealth and influence.

As the earliest days of oil boomed and Bartlesville swelled, the need for recreation in the area became apparent. The first mentions of a country club came in early 1908, when E.F. Blaise formed a committee of interested parties. Judge J.J. Shea was appointed to organize the club, with stock dues valued at $100 per share. On December 11, 1908, the Bartlesville Country Club was incorporated, with plans to lay out golf links the following year. Frank Phillips was elected as an inaugural officer of the club. Almost immediately, however, the club ran into roadblocks. By March of 1910, the officers and membership had still not settled on a permanent home. This matter would linger another year before firm plans were decided on.

It wasn’t until March of 1911 that L.E. Phillips claimed, “I have found the most available spot in the country for a country club.” Upon his suggestion and the approval of the club’s officers, plans for the first golf course in Bartlesville were laid. An organization comprised of stockholding members purchased a parcel of land from Pawhuska’s Paul Mason. The allotment was three-quarters of a mile west of the Osage / Washington County border line, on the Pawhuska Road (present-day Frank Phillips Boulevard). The site was “just beyond the mound,” near the present-day Bartlesville Municipal Airport. The club, which hired the services of Scottish-born George C. Fernie of Independence Country Club to lay out the course. L.E. served on the club’s original Board of Directors and was charged with traveling to Kansas City to gather ideas for the construction of a clubhouse. When bids for the construction were reviewed, the contract was awarded to local firm Hatcher and Moffet at the price of $4,200. On Wednesday, Nov. 29, 1911, the game of golf in Bartlesville was born. Invitations to the opening ceremonies were sent to delegates as far as Muskogee and Independence, Kansas. In preparation of the festivities, the Morning Examiner noted, “The ground (is) shaved, shampooed and manicured, so to speak, and a golf expert has laid out the links which have been pronounced by those who know to be the most perfect and complete in the entire southwest.”

Original members of Bartlesville Country Club included Huntington B. Henry of Henry Oil and Gas Company, Henry Vernon Foster of the Indian Territory Illuminating Oil Company, attorney John H. Kane, judge J.J. Shea and of course, the three Phillips brothers – Frank, L.E. and Waite.

Original Bartlesville CC

This original nine-hole, par 35 track featured one water hazard off the first hole and five mounded bunkers (some with sand in them). As it was outside city limits, Judge Shea offered his car as public transportation to the club.

The honeymoon between the club and its members was short, however. Less than five months following the grand celebration, the club required $20,000 in improvements to the grounds, golf course, clubhouse and furnishings. What took less than $5,000 to create now ballooned in cost. By the summer of 1912, William Brown, another Scot, had been hired to take over as the club professional. Golf course maintenance was by committee, and the membership added bunkers on the seventh and ninth holes. The track stretched to 3,100 yards and the greens were covered with “well-oiled sand.”

The next few years proved rocky for Bartlesville’s first club. As it was outside city limits, the site demonstrated to be significant effort visit on a nice day, and nearly impossible with rain or other inclement weather in the forecast. Financial concerns of upkeep mounted, and membership began to hemorrhage. By June of 1915, what remained of the membership began discussions of moving the club to a more appropriate and accessible site near Tuxedo Park. Instead, it was decided that the Bartlesville Interurban Railway would run a route out to the site of the club and it would be reorganized as the Oak Hill Club. Frank, as an elected member of the Interurban’s board of directors, was integral in the establishment of this line.

It was also during this time that Frank began to show interest and leadership in the club. When a committee representing Henry Latham Doherty’s Cities Service Company – which would later become the Citgo Corporation – visited town, a luncheon in their honor was to be held at the club. When inclement weather washed out their plans, Frank offered his home on Cherokee Avenue to host the event on short notice. Doherty’s representatives were impressed that one could host nearly 70 men on short notice without importing so much as a single piece of silverware.

By the early 1920s, the road to the club had once again fallen in disrepair, but Oak Hill was thriving. Local newspapers were filled with notices of dinner parties and other fine affairs at the club. Ed Dudley had taken over at Oak Hill as head professional, coming from a similar position at Miami, Oklahoma’s Rockdale Country Club. He would spend three or four years in Bartlesville, marrying the daughter of Mr. and Mrs. W.F. Johnson before becoming the head professional at Pawhuska Country Club. Dudley would go on to have a successful career in golf, winning the Oklahoma Open twice, finishing his career with 11 Top-10 finishes in major championships and boasting a 3-1 record in Ryder Cup matches. Off the course, he would accept a position to be the head professional at Oklahoma City Golf and Country Club before answering the call to be the first professional at Bobby Jones’ Augusta National Golf Club in 1932, a position he would hold until 1957.

Ed Dudley and Bobby Jones

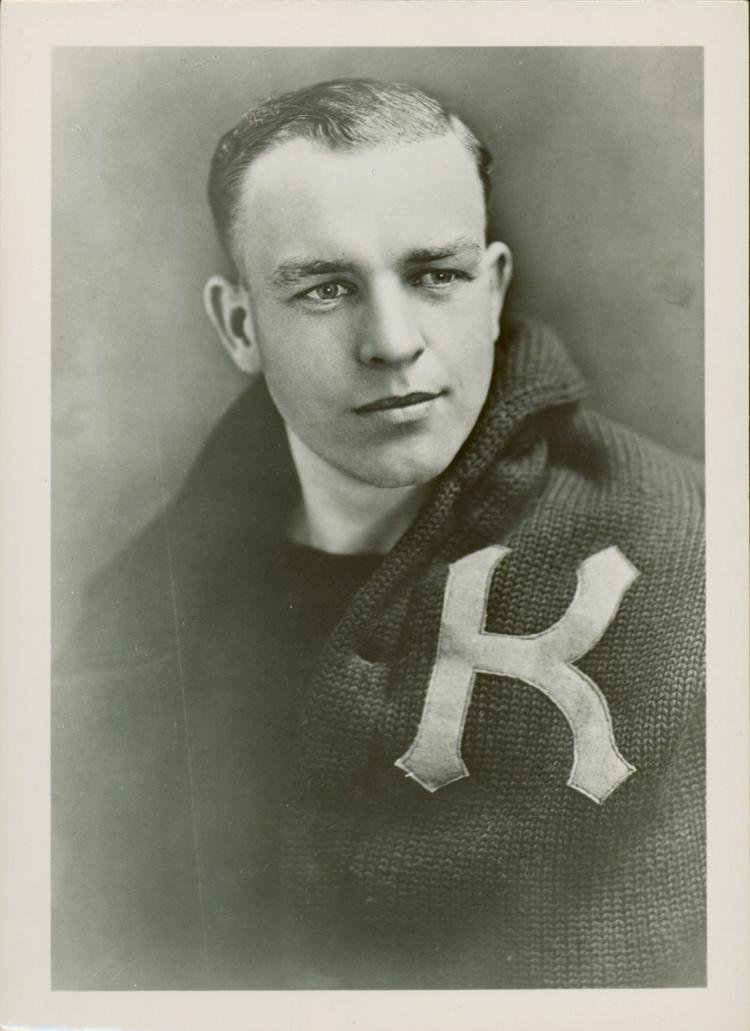

But despite the dinner parties and nine-hole amusement that Oak Hill provided on the other side of The Mound, a small group of influential men in town believed Bartlesville was ready for a more refined establishment. Frank and H.V. Foster, both members of the original club, put their best men on it. For Frank, that meant tabbing Paul Endacott for the project. Paul was born in Oklahoma but grew up in Lawrence, Kansas. As a child, he spent time at the local YMCA learning the game of basketball from Dr. James Naismith. He would go on to play for Phog Allen at the University of Kansas, leading his team to two national championships and earning national player of the year honors. As a student at K.U., he heard L.E. Phillips speak at a banquet and he decided to pursue a career with Phillips Petroleum. After graduation, he moved to Bartlesville and began a career that would see him move up the ranks in the organization, eventually to president and chairman. But before that, Paul was tasked with finding prospective land for a new country club. When he returned to Frank, he reported on a parcel south of town hugging the opposite bank of the Caney River, surrounding the Silver Lake Delaware Indian cemetery.

Paul Endacott

By this time, Frank’s only son – John Gibson Phillips – had established himself as one of the young executive socialites of the town. With the Roaring Twenties raging across America’s high society and Bartlesville choc full of oil-rich families, a new social class of young, raffish men emerged. In Bartlesville, the “Halcyon Club” was established. This association, with John G. Phillips in the middle of the pack, enforced what was happening on the local social calendar, and who was included. If it was a new country club they wanted, it was a new country club they would get.

This spoiled egotism was always a point of contention between Frank and his son. From his earliest days in Bartlesville, John grew accustomed to Frank showering him with lavish gifts in an attempt to make up for his countless hours working. It was customary for Frank, as the head of the most popular bank in town and no less than 15 other corporations, to work 18-hour days. In his formidable years, John developed a thirst for the bottle and an intense craving to stay in the spotlight. This led Frank to many sleepless nights, frustrated with the antics of the younger Phillips.

The Halcyons ran the social scene in Bartlesville in the 20s, throwing parties for any occasion and searching for every opportunity to gamble the night away, leaving trashed out establishments and tainted reputations in their wake. Once, the Halcyons threw a “come as you are” party on a whim. One party goer – still hungover from the night prior – arrived to the party in a hospital bed. John Phillips, ever the Dapper Dan, wore his tuxedo with no shoes. He would remain barefoot throughout the evening.

The Halcyon parties were the stuff of legend, rivaled only by those fictitious Fitzgeraldian tales of Gatsby in the East. On the edge of the Osage – these privileged few weren’t to be outdone by the Boston Brahmin or Manhattan elites. And this high society wanted a new playground.

Frank and John G. Phillips

On November 4, 1925, The Morning Examiner announced that a new club would be established, and be named Hillcrest Country Club. The article stated that the club was to be positioned on the Tulsa Road, and touted rolling hills, tall trees and beautiful home sites with open spaces. John G. Phillips was appointed to the financing committee on the project, which was assessed to cost $125,000.

Oak Hill members were offered right of first refusal on stock membership to the new club at the price of $250, limited to 200 stockholder memberships. Within two weeks, the committee had sold 177 memberships to the new club. Championing the new club alongside the young John G. Phillips was Fred L. Dunn of First National Bank, M.E. Michaelson and William Dana Reynolds, oil prospector. By the end of November, the membership was capped and 30 more were left on a waiting list. The Phillips family accounted for five memberships.

But if the project was to be associated in any way to the family, Frank insisted that it would be done right. He offered a $50,000 gift to the club (more than $750,000 today) on the contingency that they spare no expense in its design and construction. With this in mind, members of the Engineers’ Club and the Bartlesville Chamber of Commerce contacted famed golf course architect Walter J. Travis to design the golf course. Travis, a three-time U.S. Amateur champion, was 64-years old at the time and in the midst of designing Sea Island Golf Club. Due to his age and his responsibilities in Georgia, The Old Man refused an invitation to visit Bartlesville without a signed agreement.

Next on the committee’s list was Albert Warren Tillinghast of Philadelphia. He had ties to the area, designing both Tulsa Country Club and Oakhurst Country Club, now known as The Oaks. Others in his early repertoire included Baltusrol in New Jersey, Philadelphia Cricket Club, Winged Foot in New York and Kansas City Country Club. Despite attempts to contact Tillinghast, he never returned communication.

And so, it was Perry Maxwell, the banker-turned-golf course architect from Ardmore, who the club retained to build the course. Prior to the decision, Maxwell made an original survey of the land on which the club was to be built and deemed it worthy of his standards to host a quality golf course. The decision to hire Maxwell was announced on January 13, 1926, the same day Frank Phillips purchased 120 American bison for his ranch located a few miles southwest of the proposed club site, making his herd the second-largest in the state of Oklahoma.

Perry Duke Maxwell

Three individuals were vying for the contract to build the Hillcrest clubhouse in early 1926. Arthur Gorman was a well-established contractor in Bartlesville, and his ties with the Phillipses ran deep. He had just completed work on the lodge the Phillips Ranch a year prior. His design plans included a nearly 18,000 square foot clubhouse, with a 30-by-40-foot dining room, an open-air porch, locker rooms for men and women, a pool, dance hall and more. The design was “dignified by a forty-foot tower.”

The second plan was submitted by Albert Joseph Love, a Tulsan who proposed a design similar to Indian Hills Club in Catoosa. His plan included a Scotch-influenced clubhouse built with native sandstone.

But the chosen architect, Edward Beuhler Delk, also had connections with the Phillips family. An expert in Spanish Colonial Revival, he had recently designed the Country Club Plaza in Kansas City. The owner of the Country Club Plaza development, J.C. Nichols, was married to the sister of John Kane, Frank’s legal advisor. This fortuitous connection led Delk to designing the south side expansion of Frank’s home on Cherokee Avenue. He would go on to build Villa Philbrook and the Philtower in Tulsa, and Villa Philmonte in New Mexico, all for Frank’s younger brother Waite. The plans Delk submitted for the clubhouse included – unsurprisingly – a Spanish / Mediterranean villa style that was immediately approved by the building committee, on which John G. Phillips presided.

By Thanksgiving, Perry Maxwell had crafted 18 holes with sand greens and Delk had completed the Hillcrest clubhouse. The club planned opening ceremonies for Dec. 11, 1926. Other prominent names on the original membership list included F.L. Dunn, H.V. Foster, Arthur Gorman, John Johnstone, John H. Kane and Harold C. Price, namesake of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Price Tower.

The club wasn’t without its hierarchy. With a final price tag of $165,000, more than half ($90,000) was given through private gifts. In a dinner with committee members for these benefactors, known locally as the “Kings of Oildom,” Frank remarked that the clubhouse was an inspiration to him and compared it to the best of New York’s finest country clubs.

John’s affinity for the bottle may have been a fortuitous turn of events in the history of Hillcrest Country Club. Many times, when his binge got the best of him, Frank would banish John from town, sending him to the Broadmoor Club in Colorado Springs to get right. It was here in 1925 that John and his wife Mildred would celebrate the birth of their second child, John G. Phillips Jr. Through this connection, and John’s position on the committee for the creation of the club, they hired Jimmy Gullane from Broadmoor to become Hillcrest’s first professional. Gullane - as were many of the state’s early professionals - was Scottish, coming to America from North Berwick in 1914 as a highly touted amateur golfer. With him, Gullane carried more than a decade of impressive experience, spending time at Merion Golf Club in Philadelphia in addition to eight years at the Broadmoor Club.

The grand opening celebration at Hillcrest was an ostentatious affair. Hundreds of industrial titans and social elites from all across Oklahoma flocked to the club for dinner and dancing. For the first dinner service, the Halcyon Club had a party of 32. Frank, L.E. and John Phillips all attended the party with their wives and guests. In an attempt to sum up the evening, the Morning Examiner exclaimed, “In size, (Hillcrest) may bow to great metropolitan organizations, but in appointment, setting and completeness, it acknowledges no master.”

Beyond the opening of the club, the Phillips name continued to dominate the influence of the club. The Halcyons hosted dinner parties and bridge contests at Hillcrest, at which John and Mildred always attended. Less than a month following the opening, John was voted onto the Board of Directors. But his leadership in the club often proved to come with the caveat of self-interest.

In the club’s infancy, and due to the reputation of the Halcyon Club’s proneness to debauchery and overstuffed pocketbooks, some of the country’s seedier characters found their way to Bartlesville. One of these was the legendary golfer-turned-gambler, “Titanic” Thompson. A native of the quaint Ozark town of Monett, Missouri, Titanic was born into a gambler’s home in 1893. Learning the trade from his nomadic father, he began hustling well-to-dos for anything they had, in nearly any game they wanted to play. Cards, dice, billiards, horse shoes…it was all on the table for Titanic Thompson.

Titanic Thompson

His golden goose, though, was his unique style of integrating golf and prop bets. He taught himself the game at a young age, and was blessed with both extraordinary eyesight and an ambidextrous swing. Armed with this skill, he would travel from club to club across the country, towing young, prodigious talent with him. He would seek out the best golfers with the fattest wallets and challenge them to a big-money round. “I’ll bet my caddy and I can beat your two best guys!” he would say. Some of his “caddies” throughout the years included a young Ben Hogan, Herman Keiser and Lee Elder.

It was said that Titanic killed five men in his life, none of which he spent time in prison for murder. In 1928, he was playing in the high stakes poker game that left Arnold Rothstein – the boss of the Jewish mob and the man who fixed the 1919 World Series – murdered for debts he incurred during the game.

And so it was this smooth-talking, blood-thirsty gambler from the Ozarks who was drooling at the prospects of easy money at the hands of Bartlesville’s wealthiest socialites. Armed with his golf clubs and a young boy named Ky Laffoon, Titanic would come to Hillcrest at least three times for some healthy competition.

In May of 1931, Thompson and a 23-year-old Laffoon arrived at the club for their first match with head professional Jimmy Gullane and city amateur champion V.T. Broaddus. More than 200 spectators followed as they watched the visitors take down the celebrated Bartians, 2 and 1. The rumored side bet was more than $5,000. Laffoon would go on to have a celebrated career in golf, participating on the 1935 Ryder Cup team and finishing with 12 Top Ten finishes in major championships.

One night during their barnstorming tour through Bartlesville, Thompson hooked up with John Phillips in a high stakes card game at the elegant Maire Hotel at the corner of 4th and Johnstone. The Maire, built to host clientele and dignitaries of the city’s barons, was celebrated across the state for its one-of-a-kind chandeliers, ceiling fans and electricity. The hotel was rivaled in Oklahoma by only The Mayo in Tulsa and The Skirvin in Oklahoma City. As if Thompson needed an easier target that night, Phillips – ever tormented by his thirst – was polishing off a bottle of 90-proof bootleg bourbon. It wasn’t long before Thompson had wiped out all the cash John had on hand in the game of Seven Card Stud, but Phillips – blinded by the bottle – wasn’t ready to give up easy. On what would be the final hand, he put up the deed to his house on Cherokee Ave., the one Frank had built for John, his bride and his family. The cards were dealt, and John never stood a chance. Titanic Thompson walked away that night with a pocket full of cash and the deed to the Phillips house.

When Frank heard about the fiasco, he was livid. Despite the gambler’s killer reputation, the elder Phillips approach him with an offer he couldn’t refuse. He bought the house back from Thompson on the condition that he never approach John Phillips again. When the deal was done, Frank put the title to the house not in his son’s name, but his six-month-old grandson’s.

Thompson would continue to return to Hillcrest for years to come, but he never again tried to go after the gullible John G. Phillips.

While a Hillcrest member for the rest of his life, Frank was more apt to spend his time at the club in the dining room rather than on the golf course. It wasn’t for lack of trying, however. Ever the overachiever, Frank would try to master the game but would become frustrated and lose his patience. In his later years, he resigned much of his free time to the ranch, later known as Woolaroc. He became well-known for throwing massive barbecues at the ranch, which were often accompanied by rounds of golf in the morning at Hillcrest.

On Uncle Frank’s 66th birthday in 1939, the Bartlesville community threw him a party that carries legend to this day, beginning with a birthday dinner at the club. More than 150 friends and associates joined him for the dinner, with speeches made by John Kane, brother L.E. Phillips and Boots Adams, who had succeeded Frank as the president of Phillips Petroleum. After the tributes, Frank stood and said, “I just want to say that there are a lot of swell fellows here. As much success as I may have enjoyed, my riches are not in worldly goods so much as they are in friends and neighbors, who have gathered here tonight. Money is worth only what it will do for my friends, my country, my state and the youth of the nation.”

As the guests stood to applaud Phillips, a massive cake with 66 candles burning was wheeled into the room. Thus began a 48-hour birthday celebration that saw the influx of nearly 30,000 people into Bartlesville and festivities that to this day are considered one of the greatest birthday celebrations ever witnessed in American history.

The Frank Phillips Men’s Club, an organization created for men employed by Phillips Petroleum, would host their annual golf tournament for years at Hillcrest.

For decades, the Phillips family left a footprint on Hillcrest and Bartlesville unable to be filled by the likes of any other. Frank continued his philanthropic efforts for the rest of his life, paying off the debts of churches and establishing the Frank Phillips Foundation, which still impacts the community to this day. He passed away in 1950, followed by the sudden passing of John just five months later. Beyond the immediate relations, the tendrils of Frank Phillips’ business dealings resonate to this day. The descendants of original Phillips Petroleum employees like Boots Adams, John Johnstone and John Kane still positively influence the Bartlesville community today.

While Frank, L.E. or John may have never set a course record at Oak Hill or Hillcrest, it’s no doubt their direct influence – and the influence of those friends, family and Phillips employees – have left its mark on the game of golf along the banks of the Caney River.